This exploratory study investigates how consumers perceive age using objective and subjective approaches. It was found that younger graders rated subjects younger than their actual age. Conversely, older graders perceived subjects to be slightly older than their actual age. Results of this study suggest that when a subjective approach is implemented for age determination, subjects affix their emotions to the evaluation. The reverse logic was applicable for the expert and naïve grader methods. They did not harbor personal stances as they were not evaluating themselves. Finally, expert and naïve grader results appeared more neutral than the self-assessment as both groups were not swayed by the implications of an anti-aging prototype, whereas subjects may have been influenced after continued use to perceive a younger skin appearance (as a direct result of its assumed efficacy).

Age and Identity

Age is astutely classified as both a physiological and psychological aspect of one’s total identity. Physiological age is chiefly defined as one’s physical condition as affected by genetics and environmental stresses. These factors are not readily controlled by the individual. Conversely, psychological age relates more to how old one feels; that is, psychological age is tied closely to one’s emotional state, which is inevitably prone to fluctuation.

Unlike physiological age, psychological age is perceived to be controllable by the individual through wellness habits, exercise, diet, etc. Current advertising campaigns, marketing schemes and pop culture showcase and encourage control over one’s psychological age, using phrases including, “I take care of myself,” “Age is just a number” and “40 is the new 20.” Emphasis is placed on consumers’ perceptions regarding age. It is more about “how old I feel” versus “how old I am.”

Self- and non-self assessments regarding age are of paramount importance to the cosmetics industry, specifically within the anti-aging category. In the year 2000, Shiseido studied the disparity between life age and perceived age of Japanese women (ages 50+), and findings indicated a 9.1-year gap between consumers’ actual and self-perceived age. That is, women ages 60 to 64 rated themselves as looking just 52. These results support the notion that consumers are highly youth-centric and place more emphasis on psychological age than life age.

With proven emphasis on psychological age, the anti-aging category has secured a strong niche market among older consumers, specifically for preserving not only a youthful appearance with a devoted skin care regimen, but also a youthful outlook and emotional state with product positioning. In other words, branding products as anti-aging, versus other non-aging specific categories, tremendously impacts consumers’ perception of their efficacy and gives the impression they are actively controlling their psychological age. Mentally, this translates as, “I can’t control genetics but I can take care of my skin.” While there is currently a well-defined market strategy for the anti-aging category, it is necessary to further investigate self-(subjective) and non-self(objective) perception regarding age, to pinpoint how profoundly anti-aging product use impacts consumers’ attitudes, opinions and overall perceptions of their age. The present study aims to do just that.

Materials and Methods

Self-assessment: Thirty-eight subjects completed this study. Subjects were recruited with the inclusion criteria of specific skin imperfections including moderate to severe wrinkles in the periorbital region as well as moderate face and neck sagging, as determined by a trained technician. Participating subjects ranged from 45- to 68-years- old. Subjects were provided with an anti-aging lotion, labeled as such, to use for the duration of the study (8 weeks). The following instructions for use were provided: Use product twice daily [once in the morning and once in the evening] on the face and neck areas.

There were four evaluation time-points in total: baseline, after 4 weeks of use and after 8 weeks of use. Subjects assessed their individual age with the implementation of a mirror. For each evaluation, subjects were instructed to appear with cleansed facial skin. However, there were no particular guidelines for non-facial regions (e.g., it was not required that subjects’ hair be obscured upon arrival). Subjects completed a self-assessment questionnaire at the testing facility for each time point. In the questionnaire, a 17-point structured scale was implemented. The scale score range was from zero, which represented 0 years younger, to 15, for 15 years younger, with a “Do not know/Not sure” option as well.

Lastly, subjects were photographed upon completion of the questionnaire in accordance with regulations provided by consumer protection agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The following guidelines were followed: Subject’s positioning, lighting conditions and distance relative to the camera, and the background were identical for both before and after treatment photos. Also, preventative measures were taken to minimize variation in subjects’ facial expressions (e.g., smiling, squinting the eyes, or demonstrating tension in facial region). To further limit variation in facial expression and ensure consistency, all subjects were photographed with closed eyes.

Non-facial regions were obscured as seen in Figure 1. Specifically, loose or visible hair was secured out of camera view to minimize bias for subsequent evaluations. Photo imaging equipmenta was used to obtain photographs of the subjects using standard light settings, UV, cross-polarization and parallel-polarization techniques. These procedures ensured high-quality, reproducible facial images.

Expert grader: Participating expert graders are trained accordingly to accurately assess a wide range of skin concerns, from dry skin to wrinkle severity. For this study, age determination was the main grading criteria. Three expert graders from an external testing facility reviewed the photographs taken from the self-assessment study. Photographs were presented in a randomized order to minimize bias. Each grader provided a “best-fit” age per subject for each of the presented time points. Finally, age ratings from the expert graders were compiled and averaged by subject and time-point. Naïve grader (consumer): One hundred and seventy-eight (178) total subjects participated in this portion of the study. The panel included naïve female consumers; that is, they received no prior special training nor were they aware of the study design. Recruitment was segmented into the following age categories: 18–35 years (53 subjects), 36–50 years (57 subjects) and 51–65 years (68 subjects).

The naïve graders evaluated approximately 120 photographs of subjects from the described clinical self-assessment study. Photographs were presented in a randomized order to minimize bias. These images were shown digitally via a computer with a 15-in flat-screen monitor.

Consumers were situated approximately 1.0–1.5 ft away from the monitor. Photographs were identifiable by a three-digit numerical blinding code only, with no indication of the time points implemented for the self-assessment study. Consumers were prompted to complete a brief questionnaire regarding the photographs, recording the three-digit blinding code on the presented photograph and their estimation of the subject’s age in said photograph. Unlike the self-assessment study, naïve consumers did not have a “Do not know/Not sure” option, thus this was a 16-point scale versus the 17-point self-assessment scale.

Results and Discussion

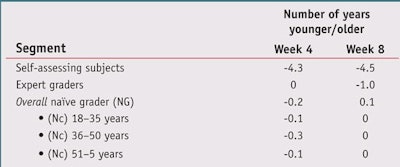

Self-assessment: Responses for “number of years younger that the skin appears” were compiled and analyzed to determine averages. Subjects who responded “Do not know/Not sure” for “number of years younger” were excluded from data analysis. Results indicated that subjects perceived themselves as looking younger after 4 weeks (by ~4.3 years average, n = 36) and after 8 weeks (by ~4.5 years average, n= 38) of treatment. At both time points, subjects noted a younger skin appearance.

As they were instructed to use an anti-aging facial lotion for the duration of this study, it can be reasoned that product use impacted these results. Participating subjects may have harbored pre-conceived notions regarding efficacy and improvement in terms of number of years younger because they were using a specific type of facial lotion. It was classified as anti-aging, which as noted can tremendously impact subjects’ perceptions of its performance and, as a result, responses seen in the questionnaire(s) at subsequent time points after continuous use.

Another explanation for these results is the self-perception of skin aging, specifically in terms of denial, vanity and self-consciousness. That is, the very premise of this self-assessment was delicate for the subjects. They were instructed to provide objective feedback on a highly subjective aspect of their identity. While responses were collected at specific time points in a controlled clinical setting, individual attitudes, opinions and perceptions regarding skin aging—in terms of “how old I am” vs. “how old I look and feel”—are prone to drastic variability. Emotional and physical states, i.e., the presence and/or lack of makeup, clothing, accessories, etc., during the assessment, can also impact results.

Further, the non-familiar, clinical-type setting in addition to subject matter may have impacted the end results. If subjects felt they were “under observation” while completing the questionnaires, especially where aging or improvement for younger skin is concerned, it may have caused a reflex-type of response, resulting in subjects rating themselves younger to quell any self- and non-self judgments regarding their age.

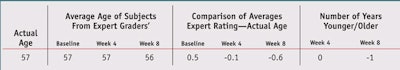

Expert graders: Results showed that expert grader ratings were highly correlated to the self-assessment findings with minimal differences. Typically, expert grading is considered a robust, objective type of evaluation. Average age scores are shown in Table 1. In this table, expert grader data was compiled and summarized. Based on the previously conducted clinical study, the average age of participants was 57 years old. Expert grader evaluations indicated that average age ratings were identical to the actual age at two time-points, i.e., at baseline and after 4 weeks. After 8 weeks, expert grader results indicated a 1-year difference vs. actual age; however, this difference is marginal and not statistically significant. These results validate the expert grader method, as their average “guessed” age ratings accurately represented the actual age data.

Naïve graders: Initially, these authors hypothesized that naïve graders, specifically those in the younger age bracket, would evaluate photographs more harshly versus older consumers. It was reasoned that younger consumers do not readily identify themselves with aging skin, and they therefore would be less likely to detect visual differences in age by photograph evaluations. By the same reasoning, it was anticipated that older consumers would provide accurate age ratings, as women in this bracket had a subjective point of view regarding skin aging. Thus, they would more easily detect nuances of the photos and pinpoint differences. Essentially, older consumers were expected to provide subjective-based responses to the photographs—e.g., aging is a steady, slow-burning process with several detectable visual stages. Conversely, younger consumers were expected to provide unemotional, objective-type responses—e.g., a “young versus old” mindset, with reduced acceptance or understanding of a gradual aging scale.

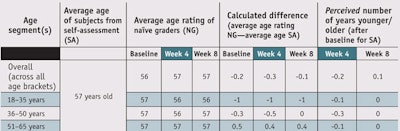

However, the data negated these hypotheses. Table 2 shows that consumers in the first bracket (18–35 years) showed no drastic or harshly exaggerated age ratings versus the subjects’ actual age. In fact, their ratings closely matched the average actual age figures. As mentioned before, participants were not aware of the various time points implemented for the self-assessment study. Despite this aspect, overall ratings showed only slight variations for each time point.

Results were then sub-divided by the age brackets: 18–35 years, 36–50 years and 51–65 years. No statistical differences were found among these brackets regarding differences between the estimated age versus actual age of the women in the photographs. However, certain trends were noted per age bracket. Women within the 18–35 age category rated photographs approximately one year younger than the actual age for each time point. Conversely, women in the 51–65 age category rated photographs slightly older than the actual age for each time point.

Implications of Subjective vs. Objective Approach

It was initially theorized that a subjective approach would elicit more lenient grading, whereas an objective approach would yield harsher evaluations, in terms of age determination. For the self-assessment, subjects had a more subjective point of view for both the product they used during the 8-week study as well as the self-evaluations they completed. Classification of their test product as an anti-aging moisturizer may have tremendously impacted the overall results. Specifically, subjects not only desired and hoped for efficacious results at the post-baseline time points, but also expected to see a difference since the positioning of the test product implied efficacious, youth-centric results. To support this reasoning, results show that subjects rated themselves an average of 4.3 years younger versus their actual age after 4 weeks of use, and 4.5 years younger after 8 weeks of use.

In the second portion of this study, expert graders were anticipated to provide more objective, technical-type evaluations in comparison to self-assessing subjects. Results proved this notion quite accurate. Also, it was observed that for “number of years younger/older,” expert grader ratings were lower than those provided by subjects in the self-assessment. After 4 weeks, subjects perceived themselves to appear 4.3 years younger, whereas expert graders saw no difference (0 years).

The disparity between these figures can be explained by the subjective versus objective approach principle. Subjects in the self-assessment study were subjective as they were asked to evaluate themselves and perceived improvement of their own facial skin. While the premise and design of the study was carried out in an objective sense, the implications of the results were highly personal to the participants. In a self-assessment, subjects were prone to affix their emotions and pre-conceived notions regarding their anti-aging test product to the evaluation.

Conversely, for the expert grader study, the reverse logic was applicable. The graders objectively evaluated the presented photographs from the self-assessment study. Expert graders did not affix their emotions or notions regarding product efficacy to their evaluations. The difference in approach, i.e., subjective versus objective, explains the extremity of perceived improvement at 4- and 8-week time points between self-assessment and expert grader results.

Comparison of Self, Expert and Naïve Assessments

Table 3 shows that naïve graders across all age brackets saw no visual difference at 8 weeks, versus a 4.5-year age difference (younger) perceived by subjects in the self-assessment study. A possible explanation is that consumers were not aware of the time points for each photograph evaluated, whereas subjects participating in the self-assessment study were clearly informed of each time point. This may have skewed the data for self-assessing subjects, as they anticipated in a linear scale of improvement over time. With the same reasoning, naïve consumers most likely had a plateau-type perception of the photographs, e.g., they did not anticipate or detect improvement over time per subject.

It is also interesting to note that the data from expert graders is more correlated to naïve consumers than the self-assessing subjects. Overall, these groups noted minimal differences at 4 and 8 weeks. In terms of a subjective versus objective approach, results indicated, as expected, that expert graders and naïve consumers evaluated the photographs in an objective manner. Conversely, subjects within the self-assessment study provided more subjective responses, especially concerning perceived improvement over 4 and 8 week time periods.

However, it is important to point out that the degree of objectivity between expert grader and naïve consumer responses varied. Examining Figure 2, one will see the variability between these groups regarding 4-week photographs. Expert grader responses exhibit less variation between the positive and negative areas of the y-axis (perception of subjects’ age). In fact, expert graders’ age ratings closely matched subjects’ actual age, displaying only 0–2 year differences for most of the individual age segments (excluding 51-years, where expert graders perceived subjects to be approximately 3 years older). Naïve graders, on the other hand, demonstrated more variability in their ratings. However, no clear trends were established regarding naïve grader ratings as younger and older age segments were perceived to be older than their actual age (and vice versa).

Figure 3 again shows that expert grader ratings produced less variability than naïve consumer ratings. Expert graders consistently perceived subjects to be 0–1 years younger than their actual age at week 8. Conversely, naïve consumers had varying perceptions of the subjects’ age on a wider, less consistent scale. They perceived subjects to be either older (0–5 years) or younger (0–6 years) than their actual age. As discussed, it is likely that the ambiguity of time points affected naïve consumers’ ratings, as they did not perceive subjects’ age on a linear-type of scale. Naïve consumers did not evaluate the photographs with a notion of improvement over time, as did subjects in the self-assessment study.

‘Standardizing’ Self-assessment Photos

It is important to note that photographs from the self-assessment were presented in a standardized manner. Specifically, photographs were taken omitting subjects’ hair and/or makeup. For subsequent evaluations with expert graders and naïve consumers, the absence of these features may have impacted age determination. Age determination is based on several individual aspects in addition to the condition and overall appearance of the facial skin, e.g., hair, makeup, facial expressions, etc. For example, a best-estimate of one’s age would ideally include the complete markup of that individual: physical appearance including both face and body; condition and color of hair; presence/absence of makeup; health-related habits and facial expressions. The photographs presented for the clinical self-assessment were an incomplete portrait of each individual, thus expert and naïve graders’ perception of age were based only on one aspect of subjects’ complete identity: facial skin.

Conclusion

Age determination hardly follows a concrete pattern. It is highly susceptible to variability since it is approached differently; i.e., objectively versus subjectively. This study indicates that individuals adopt a subjective point of view when evaluating themselves. As a result, subjects participating in the self-assessment study believed themselves to look younger at the 4- and 8-week time points. Also, since the subjects were instructed to use an anti-aging moisturizer for the duration of the study, their perceived younger look was compounded. The self-assessment findings align with Treguer’s research, which states that self-perceived age is typically younger than actual age. Conversely, when individuals are prompted to evaluate others rather than themselves, a more objective approach was employed.

Expert grader and naïve consumer ratings were similar, and it can be reasoned that the objective approach used by both had an impact on their perception of subjects’ age in the presented photographs. Also, while self-assessing subjects believed themselves to look 4.3 and 4.5 years younger, expert grader and naïve consumer ratings were lower. These findings support the notion that self-perceived age tends to be lower in comparison to non-self(other) evaluations.

Further, while expert grader and naïve consumer ratings were similar, the degree of objectivity varied between these two methods. Expert grader responses followed a more consistent pattern of grading while naïve grader responses demonstrated more variation. It can be reasoned that expert graders, by training, implemented a more technical approach, in comparison with naïve graders. Each evaluation method provided invaluable feedback to help understand the different approaches utilized for age determination. Moreover, this study validated the notion that non-self evaluations tend to be objective, e.g., expert and naive grader, while self-evaluations are more subjective in nature.

While this study highlighted differences between objective and subjective approaches, it also showcased the effects of strategic product branding, as seen in self-assessment study results. The positioning of the test facial moisturizer in the anti-aging category had tremendous implications on its perceived efficacy, and by extension, overall improvement to the subjects’ facial skin—especially regarding the “number of years younger the skin appears” at the 4- and 8-week time points.