It is no exaggeration to state: The cosmetic and personal care industry is global. Evidence to this fact spans the length of nearly any cosmetic counter; consumers can find North American, European and Asian-based brands from various companies manufacturing and selling around the globe, and these products often are labeled in several languages. While the industry is certainly international, the products they market often are not.

The logistics supporting a multinational business selling multiple regionalized products are not trivial. While the need to supply localized versions of products may be due in part to consumer preference, most often the expense of selling multiple versions of single products is simply due to differing regional regulations.

A simple example is with ingredient labeling for the word water. In the United States, the word water is required; however, only the word aqua is allowed in the European Union (EU). While Canada would accept aqua alone, if water is used, the Canadian regulations require water/eau to be listed. Thus, a fully compliant ingredient disclosure cannot be written for the United States, Canada and the EU.

The cosmetic industry has long recognized the potential for real savings from coordinated regulations and thus has initiated several programs to take steps toward harmonization.

One of the earliest programs dates to the late 1960s when the industry began work to establish a uniform nomenclature system for cosmetic ingredients. This work resulted in the publication of the first edition of the CTFA Cosmetic Ingredient Dictionary in 1973. Today the International Cosmetic Ingredients Handbook1 contains more than 13,000 monographs and is recognized as an official source for naming and ingredient disclosure by the US Food and Drug Administration2 (FDA), the European Commission3 (EC) and Canada,4 and is referenced by numerous other countries.5

One of the newest efforts toward harmonization began in September 2007 with the first meeting of the International Cooperation on Cosmetic Regulation (ICCR), a voluntary group of cosmetic regulatory authorities from the United States, Japan, the European Union and Canada. The ICCR was created to identify ways to remove regulatory obstacles among regions while maintaining the highest level of global consumer protection.6

In its first meeting, ICCR identified the need to work toward a common approach to good manufacturing practices (GMPs) and invited the industry to submit proposals on the group’s role in harmonizing risk assessment for ingredients. ICCR also recognized the importance of reducing animal testing internationally and requested agencies such as the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM), European Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM), the Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods (JaCVAM), and a knowledgeable representative of the Government of Canada, yet to be named, to assist in ensuring a collaborative approach to this issue. While it is too early to report on the results, the first indications are encouraging.

For example, ISO 22716:2007, cosmetic GMPs, has already been approved by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) as EN ISO 22716:2007 and is now the reference for European authorities. Further, this text has been communicated by CEN to all the European national standardization bodies to give it the status of a national standard by May 2008. A more complete report on ICCR activities can be found on the FDA Web site.7

While the industry has taken strides toward international harmonization, many hurdles remain before a truly international marketplace exists for personal care products.

Among the strides toward harmonization, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) stands out as a particularly important venue for advancing harmonization of personal care products.

The United States, in efforts to promote international cooperation, first hosted a conference in 1926 that initiated the forerunner of ISO, the International Standards Association (ISA). World War II halted ISA’s activities but they were taken up again after the war when 25 national standards bodies met in 1946 to form an organization to facilitate international trade through the preparation of international standards. This newly formed organization, ISO, officially began operations on Feb. 23, 1947.8, 9

It is noteworthy to mention that the short name ISO, in itself, is a symbol of international harmonization. ISO is not an acronym because acronyms would appear differently in different languages. In fact, ISO is derived from the Greek isos, meaning “equal.” Thus the organization’s abbreviation is always listed as ISO, in every member country’s language.

ISO in Action

ISO today is a nongovernmental organization composed of 158 national standard institutes as members; it is run by a centralized secretariat based in Geneva. In 2006 there were 193 active committees comprising more than

500 subcommittees, and 244 smaller working groups. The estimated operating cost for this committee structure is 120 million CHF per year, approximately US$110.2 million, and this funding is contributed by the 37 member bodies holding secretariats of the various technical committees. In addition, the member bodies provide administrative and technical services for the technical committees, equivalent to 500 full-time employees.

ISO’s mission is to facilitate international trade. This is achieved though the standards that make the requirements for participation in the global marketplace transparent. While it is clear that the primary mission of ISO is to facilitate trade, the group’s efforts to share knowledge and technological advances and to develop good management practices has a clear benefit in improving human health and safety as well.

ISO Standards

The standards themselves are developed by technical committees (TC) made up of experts representing the national standards-setting body that is the ISO member. The TC experts come from technical and business sectors, but also include experts from other areas, including regulatory agencies, testing laboratories or consumer associations.

ISO standards with which the industry is already familiar include the ISO 9000 quality standard and the ISO 14000 environmental management systems; however, the scope of ISO standard-writing activities is far greater. Indeed, TCs are working on subjects ranging as widely as standards for fasteners, three-letter alphabetic codes for the representation of currencies and specifications for freight containers. Today, ISO has a portfolio of more than 16,455 standards that are available on its Web site at www.iso.org.

It is important to note that ISO standards are voluntary and have no regulatory or statutory standing in and of themselves, but the authority of the ISO standards comes from the development process itself. ISO standards are broad based consensus documents, reflecting an agreement between international experts from all 157 participating member nations. Thus, ISO standards are widely respected, accepted by public and private sectors, and regularly referenced in regulatory activities internationally.

For the personal care products industry, the key technical committee is TC-217, formed in 2000 with the goal of developing international standards for cosmetics. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) joined the process in 2003 and has delegated the administration of TC-217 to the council.

In order to facilitate the work of TC-217, six working groups (WGs) were established to advance standards in:

- WG 1; Microbiology—writing new standards for microbiologic methods and assessment;

- WG 2; Packaging and labeling—addressing standards for labeling;

- WG-3; Analytical—developing new methods to assist countries in the anaylsis of nitrosamines and other materials;

- WG-4; Terminology—currently inactive;

- WG-6; GMP—to develop international references for implementing cosmetic good manufacturing practices; and

- WG-7; Sun protection test methods—to provide international reference methods for the measurement of sun protection factors.

Standards Development

ISO TCs use a six-step process to develop standards. The process begins with a proposal being registered as a new project (NP) and submitted to the relevant committee. The proposal is accepted as a new working item if a majority of the TC votes that an international standard is necessary, and at least five members agree to actively participate in the drafting of that proposed standard. In stage two, a Working Draft (WD) of the proposed standard is prepared by a smaller working group of experts. When they have reached a consensus, the WD is sent to the entire working group for examination in stage three. After a thorough review by the working group, the resulting document becomes a Committee Draft (CD) and is advanced to the entire committee.

The CD is discussed and upon acceptance by the whole committee, the text is finalized as a Draft International Standard (DIS). In stage 4, the Enquiry Stage, the DIS is circulated to the entire TC for voting and comments. It becomes a Final Draft International Standard (FDIS) if approved by two-thirds of the majority, and if no more the a fourth of the votes are negative. In the fifth stage, the FDIS is circulated to all ISO member bodies for a final Yes or No vote. The sixth and final stage involves publication of the International Standard by the ISO Central Secretariat. While somewhat complex, the six-stage development process helps assure, to the greatest degree possible, the acceptability of the resulting standard.

TC-217 has been quite active since its formation, publishing nine methods covering microbiology, packaging and labeling, and GMPs for cosmetics (see Table 1).

The microbiology working group has been particularly active, having issued its Seventh International Standard in July 2007. The group was featured in the ANSI newsletter following publication of ISO 18416:2007, Detection of Candida albicans. Quoting Mojdeh Rowshan Tabari, project leader and convener of the working group, “It is vital … to ensure that cosmetics have been produced with the highest standards for quality and safety before they are put on the market for consumer use.”

This new method, along with the previously published general instructions for microbiological examination and specific methods for the detection and identification of specified and nonspecified microorganisms; aerobic mesophilic bacteria; Escherichia coli; Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, will help to ensure the quality and safety of cosmetic products used worldwide.10

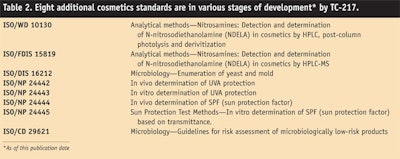

As of this writing, TC -217 has eight additional standards in various stages of development, addressing new methods for sun protection products, microbiology and analytical methods (see Table 2).

Conclusion

The scope and importance of ISO TC-217 continues to grow. This is evidenced first by the number of participating countries. The committee now includes 57 national standards institutes with 24 considered full voting members.11 Additionally, COLIPA has been recognized as an official liaison member.

More significantly, the importance of ISO is clearly demonstrated by the degree to which ISO standards are being recognized by important authorities worldwide. As mentioned previously, members of the ICCR have identified ISO 22716:2007, Guidelines on Good Manufacturing Practices, as the basis from which to advance their commitment and work toward a common approach to GMPs. More specifically, the member regulatory authorities have committed to take the ISO standard into due consideration when developing or updating guidelines or other measures addressing GMPs. To this end, the EU has already adopted the ISO Standard as the European standard, without modification; Canada will create GMP guidelines taking the ISO standard into consideration; Japan will recognize the voluntary guidelines updated in the light of ISO; and the United States will take into consideration the availability of the ISO standard as a voluntary guideline.12

Similarly, as a demonstration of the importance of ISO within the EU, the chair of ISO TC-217 was selected as convener for the cosmetics working group of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), assuring due consideration of ISO’s work within the EU Standards development process. Further, consistent with the European directive to avoid duplication of work, CEN had requested ISO to take the lead in developing sunscreen methods.13 Thus, the standards in development by ISO for sun protection methodology will eventually advance to the EU for adoption as the European Standard.

Overall, ISO has been an effective organization for advancing standards in the field of cosmetics. The methods developed promise to simplify the marketing of products by establishing well-understood and agreed upon references. Based on the demonstrated history of successes in microbiology and GMPs, it can be predicted with confidence that an increasing number of new work item proposals will emerge, advancing international harmonization to the benefit of the entire personal care products industry.

References

1. The International Cosmetic Ingredient Dictionary and Handbook, TE Gottschalck and GN McEwen (eds), Washington, DC: The Cosmetics, Toiletry and Fragrance Association (CTFA) 11th ed (2006)

2. US FDA Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR 701.3(c)(I), available at www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=701.3 (Accessed Mar 5, 2008)

3. European Commission Decision 96/335/EC, published May 8, 1996, available at eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31996D0335:EN:HTML (Accessed Mar 6, 2008)

4. Canadian Food and Drug Act, Cosmetic Regulations Section 21.2, available at: canadagazette.gc.ca/partII/2004/20041201/html/sor244-e.html (Accessed Mar 6, 2008)

5. CTFA International Regulatory Resource Manual, Azalea Rosholt, ed, The Cosmetics,Toiletry, and Fragrance Assoc: Washington, DC,6th ed (2007)

6. US Federal Register 72, 155 (Aug 13, 2007) pp 45250–45251

7. FDA Web site, International Cooperation on Cosmetic Regulation: Outcome of Meeting, Sept 26–28, 2007, available at: www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/cosiccr.html (Accessed Feb 25, 2008)

8. ANSI Web site, ANSI: An Historical Overview, available at www.ansi.org/about_ansi/introduction/history.aspx?menuid=1 (Accessed Mar 5, 2008)

9. ISO Web site, The ISO Story, available at: www.iso.org/iso/about/the_iso_story.htm (Accessed Mar 5, 2008)

10. Cosmetic Products Get a Makover; New ISO Standard Aims to Protect Against Microorganisms, What’s New ANSI newsletter (Aug 24, 2007)

11. ISO Web site, TC-217: Cosmetics, participating and observing countries, available at: www.iso.org/iso/standards_development/technical_committees/list_of_iso_technical_committees/iso_technical_committee_participation.htm?commid=54974 (Accessed Mar 5, 2008)

12. FDA Web site, International Cooperation on Cosmetic Regulation: Outcome of Meeting, Sept 26–28, 2007, published Oct 11, 2007, available at: www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/cosiccr.html (Accessed Feb 26, 2008)

13. ISO/TC 217 WG 7 N 5, Report of the second meeting of ISO/TC 217 WG 7, Cosmetics—Sun Protection Test Methods, The Hague (Oct 30–31, 2006)

!['[Sunscreen] developers will be able to innovate more efficiently while maintaining high standards of quality and safety for consumers.'](https://img.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/files/base/allured/all/image/2024/06/woman_outside_using_sunscreen_on_face_ISO_test_standards_AdobeStock_783608310.66678a92029d9.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=191&q=70&rect=62%2C0%2C2135%2C1200&w=340)