Patents have become a crucial part of how we develop cosmetic and personal care products and are becoming more and more important. They are not Nobel Prizes, but rather a core part of intellectual property that allows us to be more successful in our business. There are now more than 10 million patents issued in the United States. This is astounding when we consider that Charles H. Duell, the Commissioner of U.S patent office in 1899, stated that "everything that can be invented has been invented." Sounds like Charles may have misspoken. Why, then, do we have a patent system?

Exclusive Right

The source of a patent is no less important than the Constitution of the United States. Article I, Section 8, clause 8, states, "The Congress shall have the power to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries." The words science and useful arts actually have been interpreted as technology.

The idea that patents secure, for limited times, authors and inventors exclusivity to their respective writings and discoveries is a fundamental right. In exchange for securing this exclusive right, once it expires, everyone is free to practice the technology. There is a definite quid pro quo1—i.e., Latin for “something for something”—in the transaction. This is the basic foundation of our system.

The contract between inventor and government requires that the inventor disclose the best way to practice the technology, which is called best mode, in return for the patent. Patents also provide legal right to exclude others from practicing the claimed invention for a specified period of time. Initially, this seems to be a strange concept: the right is one of exclusion, not the right to do anything, and this causes a good amount of confusion. The right specifically is to exclude others from making, using or selling a covered invention in the United States during the term of the patent.

Today, utility patents last 20 years from earliest date of filing. Since patents do not create a right to sell a product or use a technology, that “right” comes from not infringing upon a valid patent claim.2

Public Development

The rest of the population, other than the inventor, is obliged to take the information in the patent once it expires, as it was purchased for the public by granting the initial monopoly, and intended to further develop the arts and sciences. Since the U.S. government looks dimly upon monopolies—baseball perhaps being a notable exception—the patent system imposes a duty upon the public to use the technology disclosed in a patent after it expires or as information for new inventions during the life of the patent.2

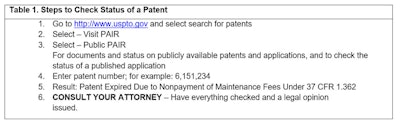

Most commonly, the information from the patent can be used without infringement by waiting for the patent to expire. Another approach is to see whether the required maintenance fees are paid to keep the patent. If the fees are not paid, the patent rights cease. However, there is a possibility to revive a patent that has expired is the fee is paid in a timely manner. The status of patents can be determined by the USPTO website (see Table 1).

Patent Invalidity

Patent InvalidityA final word on validity. The validity of a patent may come to an end in a number of ways; one being when the patent is legally challenged. The Patent Act provides that an issued patent is presumed valid, however, and the burden of establishing that a patent is invalid rests with the person asserting its invalidity.4 Since all patents are assumed to be valid, this can be a difficult and expensive undertaking.