Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is the medicine that can be used for preventing and treating diseases, the application of which follows traditional Chinese principles and philosophies.1 It is an approach to health that treats the human body as an organic whole. It holds that although viscera and tissues in the body have individual functions and responsibilities, they also coordinate to maintain normal life activities. Furthermore, TCM considers the human body and its external natural surroundings, which are dependent upon one other as an organic whole. As a result, even body surface problems such as acne, pigmentation, abnormal complexion and dry, coarse skin are viewed as the outcome of disharmony among viscera, tissues and organs, or between the human body and the natural world.

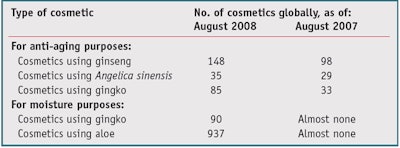

In China, TCM has been used for thousands of years in cosmetics as an important tradition that follows this theory of skin care. Research and development of using natural herbal ingredients or TCMs in skin care has grown; Table 1 compares the number of cosmetic products incorporating such ingredients in 2007 and 2008, according to the Mintel Global New Products Database.2 However, the use of these of ingredients has been controversial. Strictly speaking, TCM cosmetics are not only based on the use of natural animal, botanical and mineral materials, which are traditional TCM ingredients, as functional components, but also the formula’s prescription and formulation theories.3 In other words, TCM cosmetics are not simply made by adding TCM ingredients into formulae; most importantly, cosmetic formulas are formulated and dispatched according to TCM theories and principles—and all TCM cosmetics on the current market should adhere to this formulation concept in order to be differentiated from other products.

TCM overall is unique in its use, reflecting the characteristics of Chinese history, culture and natural resources. This article thus serves as a review of the cultural and historic aspects and characteristics of TCM in cosmetics, to assist product developers in understanding how its principles and ingredients can be combined for products targeted to this specialized market.

Historic Uses

According to archaeological records and physical evidence, the systemic use of TCM for cosmetic purposes by the ancient Chinese can be traced back more than 2,000 years. However, the topical use of specific TCM ingredients in facial care, makeup, body washing, aromatherapy, and hair and skin care was much earlier—some 3,500 years ago. For instance, per historic records by Li,4 ancient people ground up rice and applied its powder to their faces as an effective way of whitening the skin during the era of Yu the Great, i.e., 2205–2105 B.C. They also dyed the powder red and used it as blush. Particularly, archaeologists discovered more than 3 kg of puff cakes, which were made from rice and for cosmetic use, in a tomb of Eastern Han Dynasty, i.e., A.D. 25–220 in Luoyang.5 The white ground-up rice powder physically conceals facial dullness as well as enriches the skin with various types of vitamins, organic acid, proteins and monosaccharides, etc., according to modern scientific findings.

In addition, historic records such as those of Ma6 note that during the Shang Dynasty, i.e., 16th–11th century B.C., the juice of the Hong-Lan flower, i.e, Flos carthami, was coagulated and used for making blush. Called Yan-Zhi, this cosmetic was applied “for a peach blossom makeup look.” Further explanation of its use was given by Cui7 of the Western Jin Dynasty, i.e., A.D. 265–316, in which he described Yan-Zhi as a plant that grows in Western areas, bears thistlelike leaves, dandelionlike flowers and was often used to dye face powder to redden women’s cheeks. Yan-Zhi is a typical type of TCM botanical. It contains not only natural red and yellow pigments that can be used for dye, but also flavonoids, some trace elements and glycosides, which help soften the skin.

Several other historical facts prove that the ancient Chinese also made cosmetics using lead compounds or animal fat—other examples of TCM materials. Lead powder in particular has a long history of use as a foundation since it makes the skin look whiter. According to historic records given in Yong Le Da Dian,8 women began to apply lead powder as facial makeup around the time of King Wen of the Zhou Dynasty, i.e., 1099–1050 B.C.

Historic References

In most cultures including the Chinese, the origin of makeup and cosmetics is often connected with religious or social etiquette, which is reinforced by society via human aesthetic consciousness. This is evidenced among ancient ruins of the Shang Dynasty, wherein oracle bone inscriptions defined beauty, makeup and bathing (see Figure 1).9 Beauty was likened to a woman in a gorgeous, feathered hat; making oneself up was described as a beautiful girl decorating herself and looking into a mirror; and taking a bath was described as a person cleaning himself in a container filled with water.

The use of TCM in cosmetics is derived from medicinal and pharmaceutical applications, as numerous Chinese medical literature references, materials and books from the pre-Qin to the late Qing dynasties, a span of more than 2,000 years, demonstrate. In fact, only counting TCM references preserved in written form, to the present day, there are more than 2,300—several of which record the use of TCM theory in makeup, skin care, hair care and Chinese herbal medicine raw materials, methods, formula uses, manufacturing and treatment processes. The earliest preserved reference known is Wu Shi Er Bing Fang,10 which was unearthed from an ancient tomb of the Western Han Dynasty, 206 B.C.–A.D. 8, in Changsha, Hunan Province. This work recorded more than 100 types of TCM, including prescriptions for anti-acne and skin whitening, providing evidence of topical applications of TCM and TCM principles during the period of Spring and Autumn and Warring States, 770–221 B.C.

In another book, Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing,11 written during the Qin and Han dynasties, circa 221 B.C.–A.D. 24, some 365 types of TCM ingredients for external or internal use were recorded, specifying more than 160 cosmetology functions. This book also explained in detail the functional and cosmetic effects of such materials as Artemisia stelleriana, Bombyx batryticatus and Semen benincasae. Specifically, Artemisia stelleriana can be taken to expedite hair growth, improve eyesight and defer senility; ingesting Bombyx batryticatus can help eliminate speckles and reduce complexion dullness; and Semen benincasae, when applied in a facial cream, has skin-brightening and anti-aging effects. It was around this same period when for the first time the medical text Huang Di Nei Jing12 proposed a connection between inner and outer parts of the human body and between human beings and nature, which laid the foundation for future TCM cosmetology theories.

The Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang,13 A.D. 4th century, is a good representation of ancient writings of TCM in cosmetics and records both topical and oral prescriptions for “beauty-damaging diseases.” Note that beauty-damaging disease defined in TCM theory has a wider scope than the skin diseases under modern cosmetic concepts. While both are connected with diseases such acne, pigmentation, complexion dullness and loose skin, the former also includes symptoms such as scabs and warts.

Later, in A.D. 5th century, Tao14 further expanded on the 365 types of TCM ingredients from Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing to 730 types, with reclassification and rectification. Chao15 of the Sui Dynasty, A.D. 581–618, summarized and categorized diseases that affect beauty, elaborating on their causes and mechanisms. For instance, according to his work, satiation with lack of physical exercise would lead to a failure of detoxification by internal organs, the symptom of which is the appearance of brown freckles on the face.

The use of TCM in cosmetics also is believed to have gained great popularity both in royal courts and among the common public during the Tang Dynasty, A.D. 618–907. For instance, Wang16 collected and documented more than 200 prescriptions, topical as well as oral, for treatment of various beautydamaging diseases in a specific section of his book Wai Tai Mi Yao. One topical example is to grind up Semen persicae with Oryza sativa liquid to create a type of facial cleanser for skin-brightening. Another noteworthy fact of the same dynasty is that the Xin Xiu Ben Cao17 was the first official pharmacopeia in China and the world. Mainly based on Tao’s works, it recorded 850 types of TCM ingredients, referenced to various other ancient medical works, and included supplementary explanation as well as illustrations.

In relation, during the Song Dynasty, A.D. 960–1279, the mechanism of various types of diseases are systematically discussed and 16,834 prescriptions were recorded in Tai Ping Sheng Hui Fang,18 of which more than 300 concerned antiacne, skin care and whitening, hair care, aromatherapy, etc. In particular, the Yun-Mu Cream composed of mica and Semen armeniacae were used externally on the face to relieve black spots and acne. Mica and Semen armeniacae were used to clear lung heat, purge away wind-dryness as well as to moisten the skin. Further, Sheng Ji Zong Lu19 of the same dynasty documented more than 20,000 prescriptions for specific classifications such as face, body and hair, and a large number of both topical and oral cosmetology formulae, while explaining the causes and mechanisms of various beauty-damaging diseases such as freckles, chloasma, acne, warts and white scales.

The medical expert Xu,20 of the Yuan Dynasty, A.D. 1271–1368, recorded a number of TCM-based royal cosmetic nostrums from the Song through Yuan dynasties, both topical and oral, in Yu Yuan Yao Fang. This was the first book compiling thousands of medical prescriptions used only by royalty that were made known to the general public. More than 180 cosmetology prescriptions are included, most of which are topical ones accompanied with directions for use. Examples include “Qi Bai Gao,” a type of facial cream for skin-brightening and smoothing purposes; and “Dong Gua Xi Mian Yao,” i.e., Benincasa hispida facial cleanser, for deep cleansing of the skin and the reduction of skin dullness.

Similarly, in early 15th century, Prince Zhu21 of the Ming Dynasty compiled records of some 60,000 medical prescriptions, including 747 topical or oral cosmetology prescriptions with discussions of pathogenesis, and put them into categories such as by body parts or forms. It was in this reference that the term beauty cream was used for the first time. Also, one particular prescription named “Ying Ji Ru Yu San” mentions that a facial cleanser can be made by grinding up seeds of Vigna radiate, Oryza sativa var. Glutinosa, Gleditsia sinensis, Rhizoma bletillae and other selected TCM ingredients in certain proportions to make a cleanser that would effectively moisten the skin, control oil on skin and dispel acne.

In relation, in the 16th century, in his well-known Ben Cao Gang Mu, pharmacologist Li22 compiled records of more than 1,892 kinds of TCM pharmaceuticals and more than 11,000 prescriptions after several decades of effort, in which quite a few are beauty prescriptions gathered from the general public. Selected examples include: a gentle application of pearl powder onto one’s face to give the skin a more healthy and beautiful look; decocting lithargyrum with milk and applying the mixture onto the face to brighten the skin and remove existing scars; and, applying ground powder made by the roots of Trichosanthes cucumeroides (ser.) maxim. onto the face each night to effectively reduce complexion dullness.

The development of TCM pharmacology, as well as TCM cosmetics, is considered to have reached its peak of ancient times during the Qing Dynasty, A.D. 1644–1911.23 Wu24 wrote on a wide range of medical subjects including internal medicine, surgery, gynecology and pediatrics—especially recording various prescriptions and empirical formulae in the form of rhymes and explaining beauty knowledge using illustrations. For example, in the topical prescription named “Shi Zhen Zheng Rong San,” Fructus gleditsiae abnormalis, Spirodela polyrr-hiza schleid and fruits of Armeniaca mume sieband are prescribed to treat freckles. During the Daoguang Era, A.D. 1782–1850, Bao25 and Mei collected and referred to medical prescriptions and empirical formulae used by the general public daily and categorized this information by body parts in Yan Fang Xin Bian. This piece of work also referenced original anti-wrinkle, skin care and whitening formulas. For instance, washing the face using a mixture made by Radix asparagi and honey was said to make the skin whiter and fairer.

Through research in these TCM references of the past thousands of years, it is clear that the use of TCM in cosmetics was tightly connected to pharmacology in Chinese history, and that the development of TCM cosmetics from time immemorial has shifted from simple to complex, from few to various types and forms, and from serving the minority to reaching the multitudes.

TCM Cosmetic Classifications

As noted, there are thousands of TCM prescriptions in more than 2,300 historic TCM literary records and books, most of which can be found in today’s modern cosmetic products. As ancient TCM prescriptions were classified in various ways, today’s concepts can be classified by use, function and material, such as by:

- application site, such as the head, face, mouth, lips, hair and facial hair, inhalation (i.e., aromatherapy), hand and foot;

- function, such as whitening, moisturizing, antiwrinkle, mouth deodorizing, teeth-protecting, scab and wart removal, anti-acne, foot and hand rhagades;

- method of use, e.g., rubbing, bathing, grinding;

- product type, including face cream, hand cream, lipstick, ointment, blush, hair shampoo and conditioner, aroma/ incense face powder or powder, mask powder, washing powder—typically made of bean flour for body, hands or face cleaning; face cleansing powder, ornaments/vignettes to paste on the face or stick onto hair, eyebrow paint, decoction for bath, etc;

- eyebrow shape, such as the mandarin- duck-eyebrow, hill-eyebrow, Five-Sacred-Mountain-eyebrow, Three- Peaks-eyebrow, pending-pearl-eyebrow, crescent-moon-eyebrow, mist-eyebrow, floating-cloud-eyebrow, reversedblending- eyebrow and swallowtail eyebrow;26

- lip makeup styles, including Yan-Zhi blend, charming pomegranate, crimson spring, light red spring, tender Wuxiang, half bashfulness, dewdrop, pale red core, gradated scarlet, etc. (see Figure 2);27

- color in general;

- ingredient content, such as the minerals mica, black lead powder, mineral wax, talcum, jade powder, gold powder and ferric oxide; animal materials such as cattle, sheep/pig fat, donkey skin, and pearl; botanical materials such as plant roots, stems, leaves, seeds and starch; and

- packing materials, such as pottery, stoneware, porcelain, jade ware, bamboo ware, lacquer ware (i.e., wooden containers coated with lacquer), gold and silver wares, etc.

It is worth noting that most ancient TCM cosmetics not only served cosmetic functions, but also aimed to treat beauty-damaging diseases. Limited by technology, it was not possible to conduct toxicity research during ancient times. However, through thousands of years of experiment and clinical use, Chinese consumers summarized their empirical findings on toxicity and the safety of TCM ingredients in various medical works, which have been found to be consistent with modern toxicity research conclusions. For instance, arsenic is recorded as an extremely poisonous drug in Ben Cao Gang Mu.22

Ancient Prototypes

While modern cosmetics generally cannot claim to provide medicinal benefits, the manufacturing procedures of ancient cosmetics served as prototypes for modern cosmetics. For instance, one formula for treating dry and cracked lips and its preparation was recorded by Wang,16 in which the author describes the production of an early form of lipstick or “mouth grease.” From this description, it is clear that the ingredients and production of ancient lipsticks laid the foundation for modern lipsticks. The text, described below, provides production instructions based on units of measure from the Tang Dynasty, where 1 qian = ~ 3.73 g, 10 qian = 1 liang, and 16 liang = 1 jin. Also, 1 chi = ~ 30 cm, and 1 chi = 10 cun. In addition, Jiajian is a kind of TCM mixture that contains Turbo cornutus solander, musk, plant ashes, wax, etc., and is perfumed.

According to the text, 1 jin and 5 liang cinnabar powder is first ground with 7 jin wax, to which 11 liang Lithospermum are added and decocted to color the wax. The residue is then filtered out and the formula is cooled. The wax is melted on hot ashes, to which Jiajian is added and mixed until uniform to adjust the hardness; more Jiajian is added if too hard, or more wax is added if too soft. One can judge the hardness by sampling the mixture with the point of a knife. The Lithospermum blend is heated in a copper pot and poured into two bamboo halves held together like a tube. The wax is then cooled to complete the mouth grease.

To make the bamboo molds, 1.5 cun of dry bamboo head is cut away to obtain a length of bamboo measuring 1 chi by 2 cun, leaving no bamboo nodes. The bamboo is split into three parts, removing the middle, and the outer two pieces are glued back together tightly by coating cold Jiajian along the gap in the joint. The bottom and sides of the tube are wrapped with four-layer paper to prevent leaking from the gap. The tube is then fastened with rope before the melted mouth grease is poured into the tube and cooled before untying the wrap. The text instructs users to take about 40% of the grease out of the tube and cut it with a bamboo knife to make the stick head flat and smooth, then to wear it as needed.

TCM Principles in Cosmetics

As noted, one of the most important aspects to incorporating TCM in cosmetics is the adherence to one or more specific prescription philosophies and formulation theories, such as those described here in brief; readers should note that a comprehensive review of all TCM principles and practices is beyond the scope of this article.

Yin-yang: First, TCM in cosmetics is typically based on the yin-yang theory of balance, an important concept in TCM theory—i.e., that the viscera, tissues and life activities of the organic human body as a whole have two opposite and interdependent aspects, yin and yang, which maintain a dynamic, mutually consuming and increasing relationship. Under certain conditions, these aspects transform into the opposite aspect but once the balance is destroyed, the human body will turn toward a pathological state—including beauty-damaging diseases. This yinyang balance theory, which is achieved by strengthening interior balance to improve superficial conditions, such as by restraining, enhancing and reconciling inner viscera, etc., is embodied in nearly all TCM cosmetic products.

According to TCM theories, preponderance of yang would result in the over-excitment of body functions and generation of excess energy, referred to as “heat,” which may cause beauty-damaging diseases such as solar dermatitis and seborrhea sicca; while excessive yin would lead to a status of excess “cold,” represented by functional disturbance or hindrance, insufficient energy and accumulation of pathologic metabolic waste, and could cause diseases such as chilblain. Furthermore, deficiency of yang would lead to relative excess yin, causing problems such as protracted skin ulcers and dryness and cracks in the skin. Inadequate yin, on the other hand, would result in relative excess yang and may cause external skin issues such as freckles, chloasma and alopecia areata.5

Moving toward the treatment or prevention of beauty-damaging diseases, cosmetics using TCMs are formulated based on concepts such as:

The Four Natures of Chinese Medicine28—i.e., cold, hot, warm and cool, are different properties of medicine. Medicines considered to be cold or cool generally have the effect of clearing heat, purging pathogenic fire, cooling blood and detoxification; while medicines of hot and warm properties usually help clearing away cold, tonifying Qi, warming and activating meridian and nourishing vitality. Some medicines are regarded as neutral or mild in nature.

The Five Flavors of Chinese Medicine28—i.e., pungent, sweet, sour, bitter and salty, initially means the direct sensation experienced when tasting, and later includes the medicinal functions as well. For example, medicine of pungent functions can dissipate stagnation, promote blood circulation and moisturize dryness; medicine of bitter functions to purging fire and clearing damp; and medicine of salty functions has the properties of softening and purgation.

The Four Directions of Medicine Actions28 in the human body, are ascending, descending, sinking and floating. Medicines of ascending and floating generally function to invigorate yang, to disperse or diffuse, and to serve as emetics, while medicines of descending and sinking help suppress hyperactive yang, clearing heat and purging away pathogenic fire.

The Prescription Rule28—i.e., monarch, minister, assistant and guide, summarize the different roles that each type of medicine plays in the prescription. In particular, the monarch plays the most important part in the treatment, focusing on the primary symptoms; the minister reinforces the treatment efficacy and gives remedy for any concurrent diseases; the assistant serves as an supplementary role and relieves any possible toxicity or intensity; and the guide channels the direction of each ingredient and harmonizes their medicinal properties.

The Diagnosis and Treatment Rule28—i.e., principle, method, prescription and medicines, referring to the key treatment procedure steps as follows: first, to understand the cause and mechanism of the disease according to TCM theories; then, to determine the corresponding therapy; to select the most effective prescription; and finally, to confirm details of the prescription, such as proportion of each ingredients, dose, etc.

To illustrate the application of these concepts in cosmetics, consider the TCM treatment of freckles as an example. It is generally considered in TCM theory that freckles are due to wind-pathogen, wind-dryness, lung heat or phlegm, and fluid retention in the human body. Fructus gleditsiae abnormalis (mild and pungent), Spirodela polyrrhiza schleid (cold and pungent) and fruits of Armeniaca mume sieband (neutral and salty) thus can be combined together, by proportion, and applied externally to effectively clear heat, dispel wind, purge dryness, eliminate phlegm retention and moisten the skin, thus solving the skin problem. This prescription was recorded by both Li and Wu;22, 24 the latter of which is known as Shi Zhen Zheng Rong San, which was previously mentioned.

Finally, like TCM for medical purposes, when TCM ingredients and formulas are applied in cosmetics, their effects on the human body as an organic whole should be considered. As described earlier, although the viscera and tissues in the body have different functions and responsibilities, they coordinate to maintain normal life activities, as decribed below; for instance, the quality of skin and hair is believed to be closely related to the operation of viscera in the organs—in this case, the zang and fu viscera:29

Five zang organs: heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney;

Six fu organs: gallbladder, stomach, large intestine, small intestine, triple energizer, bladder;

Triple energizer: upper energizer, middle energizer and lower energizer (see Triple Energizer);

Five constituents: vessels, tendons, muscles, skin and bones; and

Nine orifices: the tongue, eyes, mouth, nose, ears, external genitals and the anus.

With the example of zang-fu organs, based upon TCM theory, they are more than anatomy; they are also the relationships between organs and viscera, and with the five constituents and the nine orifices. In particular, the quality of skin reflects the state of the lungs, which regulate breathing, Qi and fluid metabolism. Also, the quality of head hair reflects the state of the kidneys, which control growth and reproduction and are responsible for the reception of Qi.29

In addition, TCM in cosmetics addresses the human body and its external natural surroundings, which interact with and depend on each other as an organic whole. This holistic concept explains that human beings and nature are closely associated and that skin conditions are often affected by climate and environmental factors. For example, in the south part of China, the weather is humid and hot, and the skin of the body is comparatively loose; while in the north part of China, it is dry and cold, and the body’s skin is tighter. Huang Di Nei Jing12 also notes that there are constitutional differences among individuals across regions; for example, individuals who live on the East coast eat more fish and salt but too much fish may give rise to internal heat and too much salt can cause blood stasis, resulting in carbuncles. In comparison, in the central part of China with warmer weather, people eat more but work little and as a result, they are physically weaker and more likely to be affected by exogenous pathogenic factors. Thus, geographical and individual conditions must be considered when TCM cosmetics are developed for different people.

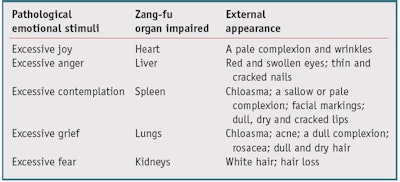

Furthermore, TCM holds that the internal physiological function and pathological changes of zang-fu viscera have a close relationship with the Seven Emotions and Five Minds—i.e., the emotions: joy, anger, contemplation, anxiety, fear, grief and terror; and the minds: joy, anger, melancholy, anxiety and fear—that result in exterior syndromes such as acne, pigmentation, a dull complexion and dry skin, which are considered to be linked to the disharmony of zang-fu viscera, tissues and organs internally, or between the human body and natural world. Normally the emotions would not cause disease but sudden, violent or prolonged emotional stimuli, beyond the range of normal physiological activities, are believed to lead to the disorder of Qi and blood activities and the imbalance between yin and yang. Since emotions are endogenous, they can directly impair the zang-fu organs, which in turn result in various skin or hair problems.28 The TCM connections between emotion/mind with external skin or hair problems are summarized in Table 2.30

Based on these holistic concepts, the ancient Chinese used TCM in cosmetics to treat beauty-damaging diseases using both internal and external therapies. Take facial markings and a dull complexion, for example. Treatment regimens included the external application of Yun-Mu Cream as mentioned previously, as well as taking Peach Blossom Pills31 (Amygdalus persica l. as the major ingredient, which can improve blood circulation and defecation), but also rest, a rational diet and harmonized mental states in addition to the coordination of states between the human body and nature—i.e., the change of climate and seasons, geographical environment, etc. All of these factors influence skin appearance, specifically dermatitis aestivale in summer and dry, rough skin in winter, resulting from the disharmony of the human body and nature.

TCM Today

Today, many cosmetic brands and products have sprung up with TCM on their labels in order to appeal to consumers seeking a closer relationship with nature, or to impart a sense that the products are safer. Some of them simply include several types of herbal ingredients in the formulae whereas others in fact are formulated using TCM ingredients and following TCM theories and principles. The Herbal T’ai Chi Detoxifying and Nutrient cosmetic seriesa is a good example of the latter, which incorporates traditional T’ai Chi concepts with TCM theories. Sales of products in this series continue to perform well in China as well as France.

In light of the great potential of TCM for cosmetics, during the past two decades, an increasing number of scholars and scientists have turned their attention toward TCM research. For example, Japanese scientists have screened 24 types of TCM ingredients such as kuh-seng and Chinese cinnamon, from relevant prescriptions recorded in Ben Cao Gang Mu, and found that they effectively restrain melanin formation in skin.32 Furthermore, Chinese researchers have found that most heat-clearing and detoxifying TCM ingredients exhibit antimicrobial effects,28 suggesting their potential use in anti-acne products.33

As studies continue to confirm the functions and mechanisms of TCM in cosmetics, relevant laws and regulations in China also have been improved. For instance, 78 Chinese herbal ingredients will be prohibited28 due to their toxicity in varying degrees, such as Radix angelicae dahuricae, which has been found to be phototoxic. On the other hand, 563 Chinese herbal ingredients such as ginseng are legally recognized for cosmetic use.34 In addition, regulations now clearly prohibit the use of medical terms or exaggerated claims suggesting medicinal benefits on cosmetic product labels.

Finally, modern techniques such as the separation of compounds from liposome membranes enables a wider application of TCM in cosmetics. With further research and steady innovation, more rapid and tremendous developments will be made in the foreseeable future.

Summary

According to the described history, categories and characteristics of TCM in cosmetics, it is not difficult to see that such cosmetics have different features and connotations from Western cosmetics. They are in a class of substances with specific meaning, emphasizing the relationship of both external and internal materiality and immateriality. The application of TCM in cosmetics is not fully accomplished by simply adding TCM ingredients into the formulating, nor by putting several natural TCM components together. The application of TCM in cosmetics is deeply rooted in several thousands of years of Chinese culture and guided by pharmacological theories; and has, moreover, been proven effective in countless works. As modern science and technology advance TCM, more and more cosmetics will be developed that better fit modern aesthetics and consumer use patterns.

Growing on the rich soil of traditional Chinese culture, the flower of TCM cosmetics is blooming with an Oriental aura. There is an old saying that illustrates the core concept behind TCM cosmetics: To retain youthful looks, benefiting Qi is most important—not decorating. If one focuses only on superficial modification, they stray from Tao (i.e., the guiding principle that brings one closer to conformity with essential nature).

References

- ZN Xia and ZL Chen, eds, Ci hai, Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House, Shanghai (2010)

- Mintel Group Ltd., TCM cosmetics will lead the fashion trend, China Cosmetics Reviews, 20 38–42 (2008)

- YM Dong, et al, Application of Chinese medicine theory and technology in cosmetics, Detergent & Cosmetics, 32(9) (2009)

- F Li et al, Tai ping yu lan, Taiping Imperial Encyclopedia (circa AD 982–983), Hebei Education Publishing House, Shijiazhuang (1994)

- XM Gao and Y Dang et al, ed, Traditional Chinese medical beauty care, China Science & Technology Press, Beijing (2000)

- G Ma, Zhong hua gu jin zhu (The Chinese ancient and modern note, AD 907–960) The Commercial Press, Shanghai (1956)

- BCui, Gu jinzhu (Ancient and modernnote, AD 265–316) Liaoning Education Press, Liaoning (1998)

- Yong le da dian, Yongle Encyclopedia, (AD 1408) Vol 6523, Guo Xue Dao Hang website: www.guoxue123.com/other/yldd/yldd2/011.htm (Accessed Jul 31, 2011)

- ZS Xu, ed, Jia gu wen zi dian. (Dictionary of oracle inscriptions), Chengdu: Sichuan Dictionary Publishing House (2006)

- JM Yan, ed, Wu shi er bing fang zhu bu yi (Variorum of the Prescriptions for fifty-two diseases), Publishing House of Ancient Chinese Medical Books, Beijing (2005)

- PJ Yang, Shen nong ben cao jing (Shennong emperor’s classic of materia medica, 221 BC–AD 24) China Academic Press, Beijing (2007)

- B Wang, ed, Huang di nei jing (Huangdi’s internal classics, 206 BC–AD 24) Publishing House of Ancient Chinese Medical Books, Beijing (2003)

- H Ge, Zhou hou bei ji fang (Handbook of prescription for emergency, AD 317–420 ) Tianjin Science and Technology Publishing House, Tianjin (2005)

- HJ Tao, Ben cao jing zhu (Variorum of the Shennong’s materia medica, AD 456–536) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (1994)

- YF Chao, Zhu bing yuan hou lun (General treatise on causes and manifestations of all diseases, AD 581–618) People’s Military Medical Press, Beijing (2006)

- T Wang, Wai tai mi yao (Arcane essentials from the imperial liabrary, AD 670–755) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (2000)

- J Su, et al, ed, Xin xiu ben cao (Newly revised canon of materia medica, AD 657–659) Shanghai Guji Press, Shanghai (1985)

- HY Wang, et al, ed, Tai ping sheng hui fang (Taiping holy prescriptions for universal relief, AD 992) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (1958).

- Z Zhao, ed, Sheng ji zong lu (General records of holy universal relief, AD 1111–1117) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (1998)

- GZ Xu, Yu yao yuan fang (Prescriptions of royal drug museum, AD 1271– 1368) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (1992)

- S Zhu, et al, ed, (2007). Pu ji fang (Prescriptions for universal relief, AD 1406) Liaoning Science and Technology Publishing House, Liaoning (2007)

- SZ Li, Ben cao gang mu (Compendium of materia medica AD 1518–1593) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (1999)

- FL Huang, et al, ed, Chinese medicine cosmetology, People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (2003)

- Q Wu, Yi zong jin jian (Golden mirror of medicine, AD 1735–1796) China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing (1995)

- XA Bao, et al, Yan fang xin bian (New compilation of empirical formulae, AD 1782–1850) People’s Military Medical Press, Beijing (2008)

- Z Fan, Dong zhai ji shi–Chun ming tui chao lu (AD 1007–1088) Zhonghua Book Company, Shanghai (2006)

- X Zhou and CM Gao, Zhong guo li dai fu nü zhuang shi (Female adornment in Chinese dynasties), Joint Publishing (HK) Co Ltd and Shanghai: Xuelin Publishing House: Hong Kong (1988)

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China, Ed, Zhong hua ben cao (Chinese materia medica) Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House, Shanghai (1999)

- CG Wu and Z Zhu, et al. Basic theory of traditional Chinese medicine, Publishing house of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai (2002)

- DH Shan, XN Zhen and DS Wang, The relationship between the theory on five minds, body constituents and zang organs and beauty, Liaoning Chinese Medicine Magazine, vol 30(1) (2003)

- SM Sun, Qian jin fang (Thousand gold prescriptions, circa AD 652) People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing (2000)

- TJ Zhu, Pigmented skin disease, Peking Union Medical College Press, Beijing (1996)

- JY Han and DX Chen, Discussion on the function of the compound for eliminating heat and toxins, Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine, 4(22) 316–318 (2000)

- TG Zhao, ed, Hygienic standard for cosmetics, Military Medicine Science Press, Beijing (2007)