The desire to appear attractive is a basic part of human nature and cosmetics have been used to this end since time immemorial, in one form or other. Like other parts of the world, Indian records for cosmetic use date far back in history, including references in ayurveda; the “Charak Samhita” or “Compendium of Charaka”—an early text on ayurveda; the epic Indian poem, “Ramayana”; Upanishads, i.e., mystic teachings on core Indian philosophies; the ancient Puranas texts on Hindu deities and other ancient writings and treatises.

Even today, Indian consumers use products associated with rituals or traditions, although some combine them with modern cosmetics, which is a result of media influence, increased exposure to the world, enhanced income, etc. Cosmetics in India are regulated by the Drug and Cosmetics Act, under which the Bureau of India Standards prescribes the requirements for given product types; kajal, for example, is covered in IS 151541 and henna in IS 11142.

Traditionally, products used as cosmetics either were natural materials or natural materials with certain modifications. These materials may be classified according to their origin, as follows.2, 3

Herbal or vegetal: Examples include sandalwood, turmeric, neem, tulsi or “holy basil,” mehndi or henna, shikakai, aloe vera, nimbu or lemon, nariyal or coconut, besan, amla or Indian gooseberry, aritha or soapnut, bhringraj, shankhapushpi, Harda, behada, attar floral essences and various flowers and oils (tailas), among others.

Mineral: Included here are clays, e.g., Multani mitti or Fuller’s earth, Chikni mitti or black earth, and Geru or red earth; litharge, i.e., lead(II) oxide; carbon and various metals.

Animal: These materials might include wax, shahad or honey, doodh or milk, dahi or yogurt curd, eggs, bird feathers and ivory.

Following is a review of the traditional types of color cosmetics used in India, including their purpose and ingredients, as well as discussions of how they have been modernized.

Sindoor

Sindoor or sindur is one of the most ancient products used by Hindu women to indicate their marital status. Married women apply this red-colored product to the part of their hair, also called maang, to symbolize each woman is happy and fulfilled and dedicated by all means to her husband. It is considered as auspicious and sacred and is meant to be worn by every bride from her wedding until the death of her husband, for his long life and prosperity. The removal of sindoor is very significant for a widow and many rituals are associated with the mother-in-law or older sister-in-law wiping it off.

In Nepal, the Sindur tree is a sacred symbol of purity. The pulp surrounding its seeds is made into pure and natural sindoor. During auspicious dates for upcoming marriages, per vedic tradition, people travel from afar to obtain the natural form of sindoor.

In the past, women used litharge-based sindoor, which has been replaced by barium sulfate, along with approved colors, giving bright red shades. Traditionally, sindoor was manufactured by mixing various ingredients and grinding them to a homogeneous powder mass, which was then filled in attractive containers or pots. Today, for convenience, the product is available in stick and liquid form, complete with an applicator.

Typical sindoor formulas are as follows:

Powder sindoor: Barium sulfate, qs to 100%; FDA-approved pigments, mostly red and maroon shades, 15-20%; preservatives, qs; and fragrance (parfum), qs.

Liquid sindoor: Water (aqua), qs to 1005; thickener, e.g., magnesium aluminum silicate,1.5-2.0%; sorbitol, 5%; sugar, 4%; and approved pigments and pearlescent pigments, 5-7%.

Sindoor stick: Mineral oil, 13%; pentaerythrityl tetraisostearate, 6%; synthetic beeswax, 9.7%; preservative, qs; approved pigments, qs; cyclomethicone, 32%; carnauba wax, 2%; and fragrance (parfum), qs.

Kumkum

Kumkum is a powder made from either turmeric or saffron—the latter of which, in ayurveda texts, is also often referred to as kumkum. It is used for social and religious markings in India to increase the fairness and glow of skin. In some areas, it is a part of bridal makeup, wherein a bride’s forehead is adorned with small white and red dots artistically applied along the brows.

Originally, Chandan or sandalwood paste and Geru or red stone paste were used to create these dots. Today, kumkum is used. To produce kumkum, turmeric is dried and powdered with slaked lime, which turns the rich yellow powder into a red color.

Currently, kumkum is available in forms ranging from liquid and powder, to paste and even stickers. When it is applied between eyebrows, as in a bindi or “dot,” described next, this is said to be the location of the sixth chakra, agya chakra, wheel of wisdom or energy point in the body. In Hindu tradition, this is considered the most sensitive part of body and is regarded as an exit point for energy. However, when products are applied to this body site, they are said to retain energy and strengthen concentration, as well as protect against demons or bad luck.

The product is available in various shades and while married women usually apply red-colored kumkum, other shades, particularly of liquid kumkum, have become a daily part of makeup routines. Powder and paste kumkum are typically available in shades of red, whereas liquid kumkum is available in white, black, red, green, yellow, purple, blue, etc. It is even available in multiple-shade packages of five, seven or 11 shades.

The manufacture of powdered kumkum is similar to sindoor, although it differs in base materials. These include starch, talc, zinc stearate, magnesium carbonates, etc. To manufacture liquid kumkum, however, a viscous gum is prepared and the color is dispersed therein.

Formulas for this product vary based on the form; some examples are included here.

Liquid kumkum: Water (aqua), qs to 100%; thicker—mostly natural gums, 1.5-2.0%; sorbitol, 4-5%; sugar, 4-5%; preservative, qs; approved pigments, 10-15%; and fragrance (parfum), qs.

Kumkum paste: Castor oil, qs to 100%; beeswax, 9%; preservative, qs; approved pigments, qs; talc, 6%; and fragrance (parfum), qs.

Kumkum powder: Starch, qs to 100%; magnesium stearate, 1.5%; talc, 1%; preservative, qs; and fragrance (parfum), qs.

Bindis

“Bindi” is Sanskrit for “dot” and refers to the dot applied to a woman’s forehead between the eyebrows.4 Besides the significance of its location at the sixth chakra, noted previously, its value is aesthetic, to adorn the forehead. Bindis traditionally are peel-off products, available in different shapes and sizes—from round, square, rectangular and oblong, to more intricate tree, snake, arrow, flower, star, etc., designs. This format is convenient to transport and re-apply. The bindi could be considered an advancement in liquid kumkum, as its development arose from the need for improved convenience.

The base material of a bindi typically is velvet, the back side of which is gummed. Apart from velvet, silk, satin and plastic materials also are used. Today, bindis are often embellished with sequins, gold dust, pearls and even stones, both artificial and/or precious. They are packaged on release paper, which is usually silicone coated.

Some traditionalists have expressed concern over the influence of Western culture curtailing the use of bindis, although in reality this is not the case. In fact, since they have reached the West, bindis are showcased by models as a fashion accessory. Manufacturers, too, have brought innovation by offering not only new designs and patterns, but also new functionality to attract consumers.

For example, this author found that some Indian women would remove a bindi and place it on a surface—i.e., bathroom and kitchen counters, walls, doors, etc.—only to re-apply it from that surface, thereby bringing contaminants to their forehead. This led to the development of bindis with antimicrobial adhesives, which have the capacity to kill microbes from such surfaces, making them safer for users.

Another example from several years ago5 is the development of bindis with analog integrated circuits, having intelligent charging capabilities for lithium-ion batteries. While their purpose was perhaps more fashion than function, such innovation keeps traditional products alive in the market.

More recently, the bindi has taken on a medical role. To improve nutrition, a simple technology was brought into a complex custom by one medical foundation in India. It joined forces with an ad agency in Singapore to combat iodine deficiency, which is more prevalent in developing countries. Together, an adhesive-backed felt bindi embedded with iodine was developed, designed to topically dispense the daily required amount into the wearer’s body.6

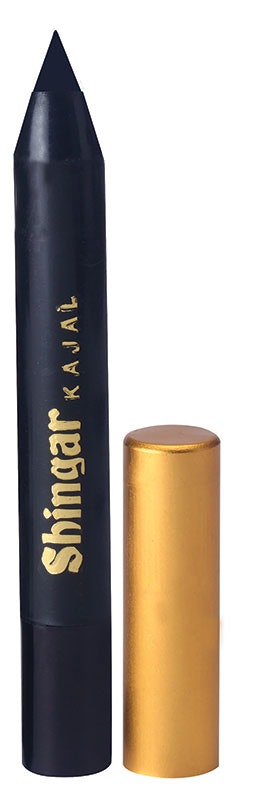

Kajal

Kajal has been used by ancient Indian women to decorate the eyes.7 It is applied to the eyelids, close to eyelashes, to enhance the expression of eyes and make them look larger and brighter. Sometimes a dot of kajal is added to the left side of the forehead or waterline of the eyes on women and children to protect them from “buri nazar,” literally “bad glance,” which can be interpreted as ill wishes or even lustful glances from others.

Note there is a difference between kohl and kajal. In India, kajal traditionally was prepared by burning ghee or vegetable oil in a bowl and collecting the soot. The soot was then mixed with additional ghee or vegetable oil, to which soothing materials such as sandalwood oil or camphor were added to obtain a black paste. Some manufacturers include additional herbs to benefit the eyes, including almond oil, castor oil, olive oil, sesame oil, licorice and Triphala—i.e., a mixture of amalaki (Emblica officinalis), bibhitaki (Terminalia bellirica) and Haritaki (Terminalia chebula), among many others.

In other parts of the world, kohl has been used and was produced by grinding stibnite, i.e., antimony disulfide, or galena, i.e., lead sulfide. Due to its high lead content, kohl is not considered safe and is therefore not permitted in many countries.

In rural Bengal, in the northeastern part of South Asia, kajal was made from Euphorbia neriifolia or the monosha plant, a type of succulent spurge. The leaf of monosha is covered with oil and kept above a burning “diya” or mud lamp. Within minutes, the monosha leaf is covered with creamy soft, black soot which has been used for thousands of years without reported safety concerns, and even applied to infants.

Today, kajal formulations have changed and incorporate carbon black as the pigment in a mixture of oils and fatty, waxy bases. The use of soothing and cooling agents, too, is still in vogue. These formulas are then filled in traditional pots, or formed as pencils or sticks. In India, kajal is reported to be the highest-selling eye cosmetic; in fact, is driving the sales of other cosmetics. As such, several international brands such as Maybelline, MAC and Faces include kajal in their current product portfolios.

“Kajal is on fire. Just last year, we sold packs of Maybelline Colossal Kajal in multiple of crores [or tens of millions]. The brand has grown five times in the last two years on the back of kajal,” said Satyaki Ghosh, director, consumer products division, L’Oréal India, in an Economic Times report.8 The company also recently debuted its L’Oréal Paris Kajal Magique line.

The popularity of kajal is echoed in the crowded western market, where the desi word kajal has become synonymous with the more familiar kohl as a descriptor of the smokey eye crayon. For example, in 2014, Guerlain launched its luxury eye liner “Khol Me Kajal” in the shade “Noir Volcanique.” The year prior, Bourjois offered its own “Queen Attitude” kohl kajal.

However, the Indian kajal market could not be left behind. From MAC’s Technakohl enhanced density product in Graphblack, to Dazzle Kajals of Chambor, and Revlon’s “Blackest Black” cosmetic, most every multinational is using kajal to gain market share in India, too. In fact, for companies such as L’Oréal and Colorbar, kajal is actually outselling lipstick by volume.9

Kajal is the perfect marriage of tradition and modernity, as consumers have been using it safely for years. While kajal was initially an unbranded segment, now several companies with large distribution networks have entered the segment, helping consumers to upgrade to branded kajal.

Alta and Mehndi

Alta: In the north and northeastern parts of India, alta is a product generally used to decorate the feet and palms. Traditionally, women used twigs, berries, bark or flowers as alta. In modern times, these have been replaced by various approved dyes that are solubilized in water and applied to skin to give the desired color; usually they are in various shades of red. While decorative, alta may be used in rituals, too, to remember a person who has passed away. For example, the feet of the deceased may be decorated with alta and an impression of them made on paper to preserve the memory of that person.

Mehndi: Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Sri Lankan women adorn intricate patterns mehndi or henna paste on their hands and feet for festive occasions, especially before wedding ceremonies. Traditional Indian designs are representations of the sun on the palm. In some parts of India, they are applied to grooms as well. In Rajasthan, for example, the grooms’ designs are often as elaborate as the brides’. In Pakistan, mehndi is often one of the most important and fun pre-wedding ceremonies, celebrated mainly by the bride’s family. Apart from marriage, in Assam, mehndi is also broadly used by unmarried women during the Rongali bihu festival.

Mehndi is used to draw artistic designs on the hands and feet, then allowed to dry. This results in a non-permanent, light orange to dark red color, depending on the additives used. Mehndi typically is prepared by making a paste of henna leaves in water with ingredients such as eucalyptus oil, clove oil, tea extract, catechu or acacia tree extract, walnut extract, apricot extract, and/or lemon juice. Mehndi may also be used to impart auburn color to gray hair.

Haldi

In India, haldi or turmeric is used for rituals, particularly before weddings. It is applied as a paste during a ceremony either the morning of the wedding or the day before the wedding after the mehndi ritual. Both the bride and groom wear the paste to bring a glow to their skin. The haldi ceremony is known by different names in different regions, such as ubtan, mandha and tel baan; it is basically an ancient Indian spa ritual, which is soothing and relaxing to the couple.

Apart from its properties of beautification, cleansing and detoxification, haldi is known to alleviate some of the nervousness the bride and the groom feel. This is due to the presence of curcumin, an antioxidant in the turmeric, which acts as a mild anti-depressant and natural remedy for headaches, and boosts immunity.10, 11 This, in effect, relieves wedding day anxiety and jitters.

Other Traditions

Apart from the described products are other forms of traditional Indian cosmetics. Tattoos or godna, for example, permanently add designs, names, letters, words, etc., to skin by means of inks.12 A “tilak,” which is Sanskrit for “mark,” also is worn on the foreheads of Hindu males, particularly Brahmins, priests and warriors. It is a mark of auspiciousness and is applied using sandal paste, sacred ashes or kumkum. Tilak-shaped bindis are available too, which women wear, but men typically use traditional paste, ashes or kumkum. Finally, similar to kajal, surma is an eye cosmetic that was brought to India by Muslim invaders and merchants. It was applied to the eyes for soothing and beautifying purposes, although it often contained lead.

Conclusions

The traditional Indian products described have been used since time immemorial. However, changes in society with respect to life style, per capita income, education and the advent of new technologies have made the world a “village.” This change is no doubt influencing the use of these products, and new generations want innovative versions of such products that are convenient and easy to use; e.g., kajal from a pot to stick, and bindis reinforced with antimicrobial adhesives. Opportunities abound.

References

- https://law.resource.org/pub/in/bis/S11/is.15154.2002.pdf (Accessed Jul 29, 2015)

- KB Patkar and PV Bole, Herbal Cosmetics in Ancient India: With a Treatise on Planta Cosmetic, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, London (1997) pp 10-50

- B Mukerji, The Indian Pharmaceutical Codex, vol I, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi (1953) pp 45-97

- KL Bhishagaratna, An English Translation of Sushruta-Samhita (176-340 A.D.), vol II, Calcutta (1911) n5-n36

- Mumbai Mirror, Times of India (Dec 15, 2005)

- gizmag.com/iodine-bindi-lifesaving-dot/36871/ (Accessed Jul 27, 2015)

- Mahabharta (critical edition) Pune, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute translation 19 (1966)

- http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-02-15/news/47358990_1_l-oreal-india-kohl-hindustan-unilever-ltd (Accessed Jul 27, 2015)

- http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-02-15/news/47358990_1_l-oreal-india-kohl-hindustan-unilever-ltd (Accessed Jul 29, 2015)

- power-of-turmeric.com/curcumin-and-depression.html (Accessed Jul 29, 2015)

- healthbeckon.com/turmeric-benefits/ (Accessed Jul 29, 2015)

- http://tattoos.lovetoknow.com/Dyes_and_Pigments (Accessed Jul 29, 2015)