*Modified with permission from: Nanocosmetics: From Ideas to Products

Women and men worldwide use an abundance of skin care and cosmetic products, in pursuit of cleanliness with soaps and shampoos, or everlasting youth with creams and serums. No matter what age, location or socioeconomic background, we are all exposed to the widespread cosmetics industry.

The global cosmetic market was worth $460 billion in 2014 and is estimated to reach $675 billion by 2020.1 While marketing and advertising efforts have forged a path for the industry’s continued growth, this momentum has not translated to equally refreshed regulatory practices in some parts of the world.

This first in a two-part series reviews the regulatory status of cosmetics, adverse event reporting and studies attempting to link cosmetics with contact dermatitis. Part II will look at specific ingredients of concern. Together, the two identify gaps for the industry and regulators to close to improve user experiences.

Brief History of Cosmetics Safety

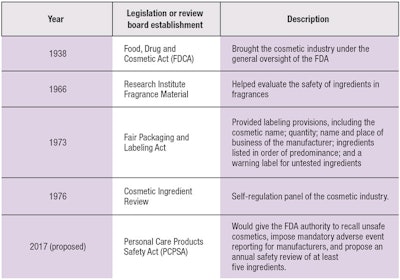

In the past, growing public concern regarding the safety of cosmetics in the 20th century prompted the U.S. Congress to enact the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FDCA). The FDCA brought the cosmetics industry under the general oversight of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; under this framework, the FDA relies on the public and physicians to alert the agency about problem products.

While select state legislatures have opted for tighter controls over cosmetics, the federal government has not enacted significant new regulatory cosmetic legislation or substantially amended the FDCA.2 Essentially, since its passing, the FDCA has only defined the term cosmetic and prohibited the adulteration or misbranding of cosmetics. In addition, the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1973 established further labeling provisions, while the establishment of the Voluntary Cosmetic Regulation Program (VCRP) helped to direct the Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR) program in prioritizing specific ingredient testing.2

Growing public concern over the safety of cosmetics has prompted regulatory measures in the past.

As of March 2017, the CIR completed safety assessments for 4,740 individual cosmetic ingredients.3 Of these ingredients, 4,611 were determined to be safe; 12 were deemed unsafe; and insufficient information was available for the remaining 117.3 However, in cases where an ingredient is considered unsafe, neither the CIR nor the FDA possesses the power to remove cosmetics containing it from the market.2

The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) also was established to help evaluate the safety of ingredients in fragrances. Like the CIR, RIFM publishes its ingredient evaluation but has no authority to remove products containing ingredients of concern from the marketplace. There is also no outside review of the primary documents upon which their reports are based. Essentially, as the industry knows, current legislation places the responsibility of determining cosmetic ingredient safety on the manufacturer of the product.

Within this setting, Diane Feinstein, a California senator, recently introduced the Personal Care Products Safety Act (PCPSA), which seeks to give the FDA authority to recall unsafe cosmetics, impose mandatory adverse event reporting for manufacturers, and propose an annual safety review of a minimal five ingredients.4 (See Table 1 for regulatory timeline.)

Surveillance Data

Adverse reactions to cosmetics can occur, although their reports have decreased over time.5 Still, some reactions are not being reported,2 so in order to encourage additional adverse event reporting, the FDA opened its reporting system—the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition's (CFSAN's) Adverse Event Reporting System—to the public.4 Since its creation, a spike in adverse events filed with CFSAN has been observed; 436 events were reported in 2014; 706 in 2015; and 1,591 in 2016.4 The most commonly implicated cosmetic categories include hair and skin care, followed by tattoos.4 Linda Katz, M.D., director for the Office of Cosmetics and Colors at CFSAN, attributes these increases to a few high-profile cases, as well as increased FDA outreach to consumers and health care professionals to report such adverse events.

The authors' personal experience, at the University of California at San Francisco, is that most adverse reactions—mainly irritant and allergic contact dermatitis—are not reported.

Cosmetics and Contact Dermatitis

As previously mentioned, cosmetic and skin care products may sometimes trigger an adverse reaction, commonly inflammation of the skin. Dermatitis is the general term used for inflammation that causes pruritis and erythema. When dermatitis is caused by exogenous materials coming into direct contact with skin, it is termed contact dermatitis.

Contact dermatitis consists of both irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), with ICD being more common and accounting for a majority of cases.6–10 While ACD is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction and requires prior sensitization, ICD does not involve the immune system and is not an allergy.11 Considerable overlap exists between the two in clinical, histological and molecular presentation.11 However, distinction between the two conditions is critical, as allergens should be generally avoided and irritants can often be tolerated in small amounts.

Cosmetics and skin care products may trigger an adverse reaction of the skin, commonly inflammation.

While it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of ACD due to cosmetics in the general population—given the prevalence is most likely underestimated since most individuals discontinue using the product and seek medical advice—studies have attempted to do so. Menkart suggested an adverse reaction to cosmetics occurs approximately once every 13.3 years per person.12 Another review found the pooled prevalence rate of ACD to cosmetics in seven different studies to be 9.8%.13

For a dramatic example, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) patch-tested some 10,061 patients with suspected ACD over seven years—23.8% of these female patients and 17.8% of the male patients reported having at least one allergic patch-test reaction associated with a cosmetic source.14

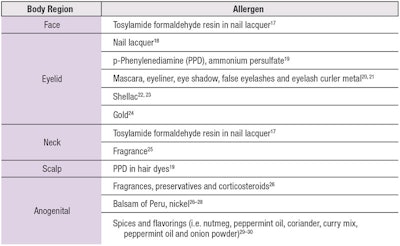

Park and Zippin outlined the frequent sites for cosmetically induced ACD and the most common allergens (see Table 2)15–30 since, for patients with ACD, the cornerstone of management is avoiding the triggering allergen. This has been made more feasible with the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1973, requiring cosmetic ingredients to be listed on packaging. However, there remain challenges in fragrances—a leading cause of contact allergy to cosmetics—as fragrance ingredients are not required to be individually listed.

Formaldehyde avoidance also appears to be difficult. In 2000, Rastogi found that formaldehyde content was incorrectly labeled in 23–33% of products tested.16

Finally, in invaluable tool for physicians and patients to manage cosmetically induced ACD is the Contact Allergen Management Program, developed and managed by the American Contact Dermatitis Society. This computerized database contains thousands of cosmetics and personal care products, so after a patient has been patch-tested and the allergen pinpointed, the offending agent may be entered into the database. From this, a list is generated of all the products that are safe for the patient to use, making it easier for patients to avoid trigger agents.

In Part II, scheduled for our November issue, ongoing contact dermatitis research and specific ingredients of concern will be explored.

References

- researchandmarkets.com/research/f2lvdg/global_cosmetics

- RB Termini and LB Tressler, American Beauty: An Analytical View of the Past and Current Effectiveness of Cosmetic Safety Regulations and Future Direction, Food and Drug Law Journal 63(1) 257–274 (2008)

- IJ Boyer et al, The Cosmetic Ingredient Review Program-Expert Safety Assessments of Cosmetic Ingredients in an Open Forum, Int J Toxicol 36(5_suppl2) 5S–13S (2017)

- M Kwa, LJ Welty and S Xu, Adverse Events Reported to the US Food and Drug Administration for Cosmetics and Personal Care Products, JAMA Intern Med 177(8) 1202–1204 (2017)

- JB Mowry et al, 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report, Clin Toxicol (Phila) 54(10) 924–1109 (2016)

- &RM Adams and HI Maibach, A five-year study of cosmetic reactions, J Am Acad Dermatol 13 (6) 1062–1069 (1985)

- AC de Groot, Contact allergy to cosmetics: causative ingredients, Contact Dermatitis 17(1) 26–34 (1987)

- HJ Eiermann et al, Prospective study of cosmetic reactions: 1977–1980, North American Contact Dermatitis Group, J Am Acad Dermatol 6(5) 909–917 (1982)

- NH Nielsen and T Menne, Allergic contact sensitization in an unselected Danish population. The Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark, Acta Derm Venereol 72(6) 456–460 (1992)

- C Romaguera et al, Patch tests with allergens related to cosmetics, Contact Dermatitis 9(2) 167–168 (1983)

- J-M Lachapelle, HI Maibach (eds), Patch Testing and Prick Testing: A Practical Guide Official Publication of the ICDRG, Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin (2012)

- J Menkart, An analysis of adverse reactions to cosmetics, Cutis 24(6) 599–662 (1979)

- KA Biebl and EM Warshaw, Allergic contact dermatitis to cosmetics, Dermatol Clin 24(2) 215–232, vii (2006)

- EM Warshaw et al, Allergic patch test reactions associated with cosmetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 2001–2004, J Am Acad Dermatol 60(1) 23–38 (2009)

- ME Park and JH Zippin JH. Allergic contact dermatitis to cosmetics, Dermatol Clin 32(1) 1–11 (2014)

- SC Rastogi, Analytical control of preservative labelling on skin creams, Contact Dermatitis 43(6) 339–343 (2000)

- R Lazzarini et al, Frequency and main sites of allergic contact dermatitis caused by nail varnish, Dermatitis 19 (6) 319–322 (2008)

- RL Rietschel et al, Common contact allergens associated with eyelid dermatitis: data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2003–2004 study period, Dermatitis 18(2) 78–81 (2007)

- RL Rietschel and JF Fowler (eds) Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis, Sixth Edition, Hamilton, BC Decker (2008)

- F Brandrup, Nickel eyelid dermatitis from an eyelash curler, Contact Dermatitis 25(1) 77 (1991)

- JD Guin, Eyelid dermatitis: experience in 203 cases, J Am Acad Dermatol 47(5) 755–765 (2002)

- CJ Le Coz et al, Allergic contact dermatitis from shellac in mascara, Contact Dermatitis 46(3) 149–152 (2002)

- T Shaw et al, A rare eyelid dermatitis allergen: shellac in a popular mascara, Dermatitis 20(6) 341–345 (2009)

- S Nedorost and A Wagman, Positive patch-test reactions to gold: patients' perception of relevance and the role of titanium dioxide in cosmetics, Dermatitis 16(2) 67–70; quiz 55–66 (2005)

- SE Jacob and MP Castanedo-Tardan, A diagnostic pearl in allergic contact dermatitis to fragrances: the atomizer sign, Cutis 82(5) 317–318 (2008)

- EM Warshaw et al, Anogenital dermatitis in patients referred for patch testing: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1994–2004, Arch Dermatol 144(6) 749–755 (2008)

- K Bhate et al, Genital contact dermatitis: a retrospective analysis, Dermatitis 21(6) 317–320 (2010)

- K Kugler et al, [Anogenital dermatoses—allergic and irritative causative factors. Analysis of IVDK data and review of the literature], J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 3(12) 979–986 (2005)

- H Vermaat et al, Anogenital allergic contact dermatitis, the role of spices and flavour allergy, Contact Dermatitis 59(4) 233–237 (2008)

- H Vermaat et al, Vulval allergic contact dermatitis due to peppermint oil in herbal tea, Contact Dermatitis 58(6) 364–365 (2008)