Looking ahead in 2025 and beyond, the cosmetic industry is going to see an uptick in global regulations. However, the U.S. may lead the way in complexity this year; and not only due to MoCRA. The following gives an overview.

In the absence of preemption at the federal level, U.S. states have been passing ingredient regulations that will make compliance more difficult. The result is likely to look like the European Union (EU) prior to the passage of EC 1223/2009. Before 2009, the various countries in the EU were able to ban or restrict ingredients at will, creating a patchwork effect – essentially making it more difficult to create a single formula for the EU.

During that time, if a compliant product was introduced into the EU, it was possible for it to be non-compliant within one year if one or more EU countries required reformulation. It is entirely possible that the industry could see this same situation in the U.S. over the next year or two.

U.S. Regulations in Motion

MoCRA: During 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Office of Cosmetics and Colors was focused on implementing the Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act of 2022 (MoCRA).1 The product listing portal opened on July 1, 2025. This, combined with enhanced attention on safety substantiation, has been time-consuming and resource-draining, impacting both domestic and international brands.

There is no doubt that the FDA will step up enforcement activities in 2025 against brands that have not listed products and begin facility inspections. Non-compliance can lead to warning letters, mandatory recalls and for foreign brands, customs holds on imported products.

MoCRA also requires the FDA to create regulations for Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), fragrance allergen labeling and standardized testing methods for detecting and identifying asbestos in talc-containing cosmetic products. (Editor’s note: During the publication of this column, on Dec. 27, 2024, the FDA issued proposed testing methods to detect asbestos in talc.)2

Formaldehyde ban, fragrance allergens: Another regulation due in 2024 was a ban on formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing chemicals in hair smoothing and straightening products. This has been delayed several times and is currently on the Unified Agenda for March of 2025.3

In addition, regulations for fragrance allergen labeling were due in June 2024; this has been pushed back to January 2025.4 At the time of writing this article (Dec. 31, 2024), no allergen labeling regulations have been announced or implemented. It is not clear when they will be published and depending on what implementation date the FDA sets, this could have a big impact on brands in 2025.

CARES Act fees: Under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act, the FDA has been given authority to collect user fees from over-the-counter (OTC) product manufacturers to support the OTC monograph program known as OMUFA (the OTC Monograph drug user fee program). Currently the FDA is looking to re-authorize OMUFA for future activities. To date, the money collected has been used to create a new IT system to support the electronic availability of OTC monographs.5

Color certification fee increase: On Dec. 9, 2024, the FDA’s fee increases for color certification services were implemented.6 The fees for straight colors including lakes will go up by $0.10 per pound. Repacks of certified color additives and mixtures will also see similar increases in fees.

FDA reorganization: While these regulatory changes are under way, the FDA has also undergone reorganization. The Office of Cosmetics and Colors has been moved from the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) to the Office of the Chief Scientist.7

According to the FDA, “The Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) provides strategic leadership, coordination and research expertise to support scientific excellence, innovation and capacity to achieve the FDA public health mission. OCS oversees FDA regulation of cosmetic products and certification of color additives for cosmetics, foods, drugs and devices. OCS leads FDA-wide scientific initiatives and develops and implements science policy in cross-cutting areas while performing applied research and regulatory testing in an expansive network of laboratories around the country.”

Hopefully, this move will allow for more integrated, well-researched ingredient regulations, including those that are currently under consideration by states. In the meantime, with the lack of ingredient preemption at the federal level, more states will be motivated to pass their own regulations.

2024: The Year of State Regulations

In 2024, the industry was given a preview of what is likely to continue in 2025 and beyond. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), lead and formaldehyde and formaldehyde donors appear to be the leading targets for state regulation. 1,4-Dioxane is not far behind.

PFAS: Undefined and in Limbo

What is currently complicating compliance with PFAS regulations is the definition of PFAS. One current definition that has emerged – i.e., “at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom”8 – is similar to the definition crafted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which has been adopted by the European Union for the regulation of PFAS.

To date, however, there is no one definition at the federal level that states can use to write regulations, nor is there a federal regulation to preempt states. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is planning to release draft regulations in the coming months, but even within EPA, there is no one designated definition for PFAS.

Having inconsistent state definitions for PFAS, or at least inconsistent exemptions, will make compliance very difficult for brands. Add to this the international definitions that could be used to regulate PFAS and compliance will become even more complex.

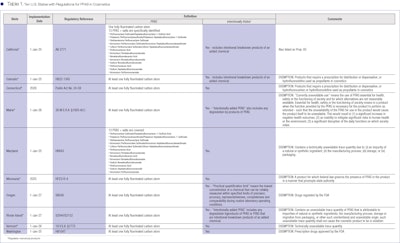

Currently, 10 states have regulations on the books for PFAS in personal care products, seven of which also have regulations for menstrual products. The states, implementation dates and basic details are listed in Table 1 (see below or view in the Digital Magazine).

Lead Limits to the ppm Trace Level

Five states have enacted heavy metals regulations focusing on lead: California, Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota and Washington. Most states have set their levels at 10 ppm (Minnesota’s is higher), which is consistent with the FDA’s approved level in colorants.9 However, Washington state has taken this to a whole new level. Without validated and reliable data, Washington’s Department of Ecology (DOE) has set the regulatory limit of lead to 1 ppm.

The WA DOE wrote a report in support of the 1 ppm limit and other chemical restrictions that combined a literature review with a 50-product test.10 The DOE purchased 50 low-cost cosmetic products including makeup, hair straighteners, facial cleansers and intimate hygiene products from retail outlets for testing. The DOE detected lead at 5.55 ppm in a dark-tint powder foundation and found lead at levels between 1 ppm-2 ppm in a pressed powder foundation and in a lipstick; thus the justification for the 1 ppm level.

The DOE also referenced separate product testing studies from non-governmental organizations, government organizations and academic research labs, the report noted. “When considered alongside reported uses of chemicals in cosmetics, these studies can fill in information gaps that exist when companies fail to report or are unaware of chemicals in products,” the department said. The report also cites regulations targeting cosmetic chemicals in other states.

From its own study and the other research, the DOE concluded: “The widespread presence of hazardous chemicals in a variety of cosmetic products means it is possible for people to be exposed to many of them through their daily personal care routine. People of color in Washington may have more exposure to these or other harmful substances. For many people of color, the negative impact of harmful cosmetics is compounded by other environmental and social factors.”

The reality is that the lead is in the formula as a contaminant from naturally occurring colorants, mica, kaolin and other mineral-based raw materials, and can vary from batch to batch. It is even possible that lead may come from plant-based ingredients grown in clay soil. But in the absence of any data on colorants, WA DOE’s assumption is that the industry is exposing consumers; particularly people of color. The question is: What will other states do? Will they follow Washington’s lead?

Formaldehyde and Formaldehyde Donors

Formaldehyde and formaldehyde donors were banned as of Jan. 1, 2025, in both California and Washington per the Toxic-Free Cosmetics Acts, while Maryland and New York have passed restrictions on the use of formaldehyde and formaldehyde donor preservatives in cosmetics. Of all the targeted chemicals in 2025, formaldehyde is the least surprising and perhaps the least worrisome from an industry perspective – unless you make hair products or use formaldehyde donor preservatives.

Hair smoothing and hair straightening products have been on FDA’s radar for some time and hair care companies have been put on notice to look for alternatives. This is not only a U.S. focus, but also international. Saudi Arabia, for example, requires products that contain keratin to be tested for 1,4-dioxane and formaldehyde as part of the registration process.

Conclusion

As regulations become more complex, the industry will need a heightened sensitivity to them – and not only in the U.S. but globally – as chemicals of concern are targeted. Brands, manufacturers, formulators and product development will need to lean in on their regulatory resources to ensure that products stay compliant.

References

1. U.S. Congress. (Accessed 2024, Dec 31). H.R. 2617. One hundred seventeenth Congress of the United States of America at the second session. Available at https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr2617/BILLS-117hr2617enr.pdf

2. Grabenhofer, R. (2024, Dec 30). FDA proposes MoCRA-mandated tests to detect asbestos in talc-containing cosmetics. Cosmetics & Toiletries. Available at https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/regulations/safety/news/22929484

3. U.S. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (Accessed 2024, Dec 31). HHS/FDA, RIN: 0910-AI83, Publication ID Fall 2024; Use of formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing chemicals as an ingredient in hair smoothing products or hair straightening products. Available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202410&RIN=0910-AI83

4. U.S. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (Accessed 2024, Dec 31). HHS/FDA, RIN: 0910-AI90, Publication ID Fall 2024; Disclosure of fragrance allergens in cosmetic labeling. Available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202410&RIN=0910-AI90

5. Congressional Research Service. (2024, Nov 20). Over-the-counter monograph drug user fee program (OMUFA) reauthorization. Available at https://tinyurl.com/tmbh4r2u

6. Cosmetics & Toiletries. (2024, Nov 11). Fees increased on U.S. FDA color additive certification; Here's what you'll pay. Available at https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/regulations/regional/news/22925992

7. FDA. (2024, Oct 10). Office of the chief scientist reorganization. Available at https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/whats-new-ocs/office-chief-scientist-reorganization

8. Pelch, K. (2024, Feb 20). The definition of PFAS should be science based. NRDC. Available at https://www.nrdc.org/bio/katie-pelch/definition-pfas-should-be-science-based

9. FDA. (2022, Feb 25). Lead in cosmetics. Available at https://tinyurl.com/mhthsspv

10. Department of Ecology. State of Washington. (2023, Jan). Chemicals in cosmetics used by Washington residents. Available at https://apps.ecology.wa.gov/publications/documents/2304007.pdf