Just as the industry began to comply with the 7th Amendment to the Cosmetic Directive, the European Union (EU) Commission proposed the new 8th Amendment. After confusion surrounding the old rules, the commission attempted to correct matters, only making them worse. Governments seem to continually make life more complicated for citizens by “simplifying” everything.

Before headway can be made on the proposed 8th Amendment, attention should first be turned to the damage caused by the 7th Amendment. The 7th Amendment was necessary because under Article 4, Section 1, Part I of the 6th Amendment, the marketing of cosmetics incorporating ingredients or combinations of ingredients that were tested on animals was prohibited after June 30, 2000, in order to meet the safety requirements for cosmetics. If alternative methods were not available by Jan. 1, 2000, an “escape” clause required the EU Commission to submit draft measures by that date. No alternative methods were available by that date; thus arose the need for the 7th Amendment.

The 7th Amendment was passed Feb. 27, 2003, and included four clauses relating to animal testing that banned:

- The testing of cosmetics on animals where a validated alternative nonanimal method is available;

- The testing of raw materials on animals where a validated alternative nonanimal method is available;

- The testing of any finished cosmetic on animals in the EU; and

- The use of animal testing in the EU for any ingredient to comply with the directive after a validated alternative method is available.

To reach this position, additional changes were made to secure acceptance by the parliament and council of ministers. These include:

1. Prototypes are now considered cosmetics. This eliminated the loophole whereby a prototype product comprising 76% of water could be tested on animals, yet the final product produced with 75% water could carry the label claim of “not tested on animals.”

This loophole also called into question the validity of inhalation safety testing for new aerosol products since the tests relied on prototypes. The supplier would test the prototype for inhalation toxicity and when the test material was found to be safe, the finished goods producer translated that product’s safety to the final product even though no studies on the final product were actually performed.

2. All ingredients classified as Category 1 and 2 carcinogen, mutagen or toxic for reproduction (CMR) are banned from use in cosmetics. Similarly, Category 3 CMRs must be approved by the scientific committee and placed on Annex III with a list of conditions and possible warnings associated with their use. Category 1 substances are known to be carcinogenic/mutagenic/reprotoxic to man, whereas Category 2 substances, although regarded as the same, are not known to be; Category 3 substances should cause similar concerns but here the available information is not adequate to make a satisfactory assessment.1

3. The EU Commission will develop guidelines for claims such as “no animal testing” or “not tested on animals” on cosmetic products.

4. The EU has identified 26 allergens principally found in fragrances or flavors but also present in essential oils and other sources. If those allergens are present in levels higher than 10 ppm in leave-on products or 100 ppm in rinse-off products, they must be part of the ingredient declaration.

5. Products that are stable for less than 30 months must have a “best if used by” date on the label. Products that are stable for over 30 months must include a “period after opening” symbol on the label with a number indicating for how long a product can safely be used by the consumer once it is opened.

6. Safety assessments of cosmetics intended for use on children under the age of three and for external intimate hygiene are required to take this use into account.

7. Product information packages must contain all data from any ingredient testing performed on animals to meet this directive or the legislative or regulatory requirements in nonmember countries.

8. Consumers may receive the qualitative formulation, purpose or function of the cosmetic, adverse reactions to human health, and the quantitative amount of any dangerous substance (as covered by Directive 67/548/EEC) contained in the cosmetic.

Results of the 7th Amendment

In regard to the first additional change to secure acceptance by the parliament and council of ministers, cosmetics sold in the EU cannot be tested on animals. This protects the safety of animals that most likely were bred for the minimum required safety testing. However, this stirs up a debate in ethics since cosmetics that are not thoroughly tested on animals are tested inadequately on human volunteers and released to be sold on the market.

It is interesting to note that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not banned the importation of aerosol cosmetics from the EU. These products cannot be tested for inhalation safety and do not carry the 21 CFR 740.10 warning stating: “Warning—the safety of this product has not been determined.” This lack of safety testing on aerosols could cause future problems. Action should be taken by the FDA soon before any consumer suffers severe adverse reactions from inhaling an untested aerosol product.

The banning of CMRs in point two is an unjustified overreaction that lacks supporting evidence because the route of exposure is not considered. This ban has struck fear in the EU Commission because the day will come when the most dangerous reprotoxic chemical and a known carcinogen—ethyl alcohol (INCI: alcohol) in both denatured or undenatured forms—is classified as it should be, as a Category 1 CMR. This is a major reason for the proposed 8th Amendment.

Because of this clause, the personal care industry lost dibutyl phthalate even though the EU’s Scientific Committee agreed that it was perfectly safe to use in nail polish and was simply unsafe for ingestion.

“Not tested on animals” and similar claims noted in the third point may end up hurting the personal care industry in the end. Even if a finished cosmetic is not tested on animals, all of the ingredients formulated in it probably have been. The most common ingredient in personal care, water, is tested on animals. These types of claims raise concern about the safety of cosmetics and ingredients because how is the safety of a product determined if it is not tested on animals? Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) already attack the industry for lack of safety.

The fragrance allergy listing change in point four has accomplished little except adding clutter on personal care labels and more work for consultants. A consumer generally does not know they are allergic to something unless they go to a dermatologist to be tested. Dermatologists use a test kit that includes a test for fragrance allergens; however, only eight of the 26 allergens are included in the kit. Perhaps the reasoning behind the fragrance allergy legislation is to slowly force the fragrance and flavor industry to reveal what is in its products. It is only a matter of time before such strictures on the ingredients in fragrances and flavors follow suit.

The PAO symbol described in the fifth change does not clear up labeling confusion in the personal care industry. The EU should first establish and publish a method for determining 30 months’ stability. It would then have to include a space on every product where the consumer could write in the date the product is opened. Finally, the EU would have to develop a set of tests the product must pass in order to label it 3, 6, 9, 12, etc., months. In an informal survey, nearly 1,000 chemists were asked if they recalled when they had opened a product and only one did. Thus, it would be safe to assume that consumers do not know when they open their cosmetics and probably are not concerned about the PAO.

The addition of point six about special attention being paid to children’s and external intimate hygiene products by the safety assessor assumes that the safety assessor is not already paying close attention to the assessment of these products. The 8th Amendment attempts to address the quality of safety assessments.

In regard to point seven, listing every animal test performed on ingredients serves no purpose. Test records generally do not date back to the safety testing performed on standard ingredients; many of the original companies that offered them have been bought and sold so many times that records cannot be found. It would make more sense for the EU to require suppliers to list all animal testing that took place after the passage of the 7th Amendment and as of a given date. Few individuals probably care about acute oral feeding studies performed 75 years ago, and this information does not add much to the product information package.

Point eight giving consumers the right to access certain information has gained little interest. The European Cosmetic, Toiletry and Perfumery Association (Colipa) initially set up a Web site for consumers to obtain this information and in five years, no one reportedly has requested this information. The purpose and ingredients are listed on the product. Cosmetics that cause severe adverse effects are quickly withdrawn from the market. It will be interesting to see what happens when NGOs lay hands on the Dangerous Substance Directive. Fortunately, this listing of chemicals is not included on the dangerous substance Web site. It also is listed by International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry names and not International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients names.

The 7th Amendment has made little improvement to the personal care industry and it has not only not improved the safety of cosmetics, it also has cost the industry lots of money. It is now time to turn toward the changes the 8th Amendment proposes.

The Proposed 8th Amendment

There are four stated objectives to this proposal:

Objective 1: To remove legal unclarities and inconsistencies. These inconsistencies can be explained by the high number of amendments (55 to date) and the absence of any set of definitions. This objective also includes several measures to facilitate management of the Cosmetics Directive with regard to implementing measures;

Objective 2: To remove divergences in national transposition which do not contribute to product safety but add to the regulatory burden and administrative costs;

Objective 3: To ensure that cosmetic products placed on the EU market are safe in the light of innovation in this sector; and

Objective 4: To introduce a possibility in exceptional cases to regulate CMR 1, 2 substances on the basis of their actual risk.2

The first objective discusses the high number of amendments. There have been seven amendments to the articles, but the majority of changes were Adaptions to Technical Progress of the nine annexes. The second objective reviews the need to unify cosmetic regulations without exceptions by all of the member states, rather than 27 different national regulations. The third objective maintains the basic concept of all cosmetic regulations—safety. The fourth objective is to address the ban of Category 1 and 2 CMRs in order to potentially allow their limited use in cosmetics. This refers to the fear of losing alcohol as an ingredient, as stated previously. The document then goes through justifications and major issues.

The first and most important point is to recast the directive as a regulation, so that each member state will have the same rules. This is a major improvement over the current directive. These new regulations only apply to cosmetics, not medicinal products or biocidal products. A product will be defined as a cosmetic on a case by case assessment. To establish clear responsibility, each cosmetic must be linked to a representative in the EU community. This is especially important for products that are not sold through importers.

The EU commission has proposed changing the information in the product information package to include the identity, quality and safety information. The submission of information to poison control centers and pertinent authorities should be completed at one location and filed electronically. Hair dye colorants will be added to Annex IV or the coloring agents allowed in cosmetic products.

CMR 1 or 2 substances may be considered for use in cosmetics if the ingredient is legally used in foods and there are no suitable alternative substances. There could also be an exception allowing the use of such substances if their use in cosmetics is considered safe by the SCCP. This is how the EU Commission is proposing to work around the possible alcohol issue.

Another justification put forth in the proposed 8th Amendment states that “the safety of finished cosmetic products can already be ensured based on the known safety of the ingredients that they contain. Provisions prohibiting animal testing of finished cosmetic products should therefore be provided.”3

This makes the assumption that all cosmetics are simple mixtures, when the safety of individual ingredients actually does not make their combinations safe. In reality, some ingredients react to form new chemicals in situ. Others provide a penetration and solvency effect on other ingredients.

Could the industry use this argument, that there are no new chemicals created in cosmetics, and apply this to REACH? Although it would make the personal care industry happy, remember it is not cosmetic chemists who are making this legislation on cosmetics.

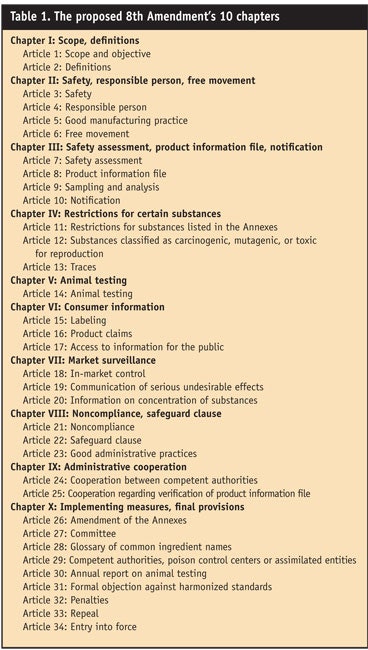

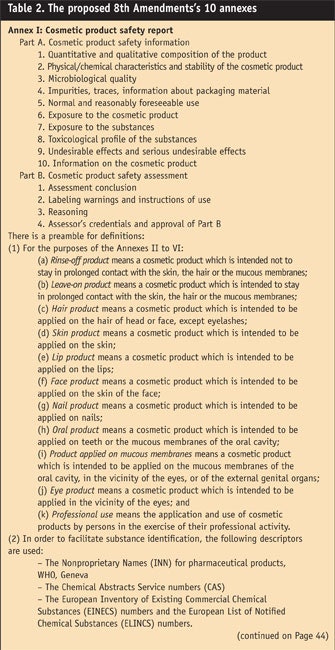

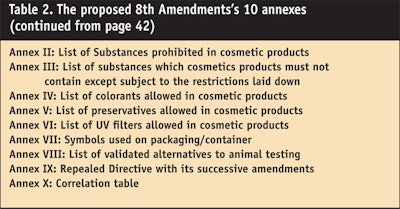

The old Directive consisted of 15 articles and nine annexes. The new regulations consist of 34 articles divided into 10 chapters (see Table 1) and 10 annexes (see Table 2 and Table 2 continued).

Discussion

It is critical to state again that these are proposed new regulations until the parliament and the council approve them. The governing bodies can, of course, make any changes they like until the new regulations go into effect. When the 8th Amendment is passed, it will go into effect three years after publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

There are some good points in these changes, the major one being that there will be one set of rules throughout the EU. Currently, each member state has a variation, making compliance difficult.

Another good point is that it corrects a regulation that was confusing in the first place. The old regulation stated that if a product contained benzophenone-3 at higher than 0.5%, the formulator was required to post a warning on the product, stating: “Contains Oxybenzone.” Consumers would see this warning, yet when they examined the ingredient listing, they would not find oxybenzone in the list because the INCI name is benzophenone-3. This has finally been corrected and under the proposed rules, the warning would read: “Contains benzophenone-3.”

This author believes the proposed changes are a giant step backward in cosmetic regulations. Besides cluttering up the regulations with a ban on 1,328 chemicals, maybe 10 of which have ever been used in cosmetics, it continues to perpetuate the EU’s attitude that self-regulation does not work.

Probably the most objectionable part of the proposed regulation is the requirement that each cosmetic must include the name of the responsible individual, not the company, and his/her address in the EU on the package. Furthermore, this person must review the product information file and the safety assessment before he/she is allowed to notify the competent authorities and allow the cosmetic to be placed on the market.

For European cosmetic companies, establishing this person is a problem but not a major obstacle. However, if cosmetic companies export into the EU, this is a major non-tariff barrier to overcome. If in the end the proposed 8th Amendment is passed, the FDA should respond by requiring EU companies to establish a similar responsible individual in the United States.

References

1. The EU Directive on Dangerous Substances, Informal Consolidated Version of Directive 67/548/EEC, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/dansub/consolidated_en.htm (Accessed Apr 30, 2008)

2. Commission of the European Communities, Regulation Of the Eurpoean Parliament and of the Council on Cosmetic Products, Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/cosmetics/doc/com_2008_49/com_2008_49_en.pdf (Accessed Feb 5, 2008)

3. Ibid Reference 2, p 16