Just as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was issuing its Proposed Rules for Sunscreens in the United States,1 Australia issued its new Cosmetics Standard 2007.2 These new standards move six categories of products from the “therapeutic drugs” arena to “cosmetics” in Australia. These changes were made after the Australian Parliament consulted with industry stakeholders.

Product Categories

The following is a breakdown of products originally considered as therapeutic drugs if they made SPF claims, and that will now be regulated as secondary sunscreens.

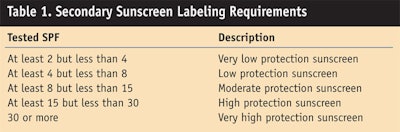

Face and nails: These products include tinted bases or foundations, i.e., liquids, pastes or powders, and products intended for application as sunscreens on the lips. These products must meet the definition of a secondary sunscreen, which is: “a product [that] is represented on the label as protecting the skin from certain harmful effects of the sun’s rays while fulfilling another primary function.”3 Furthermore, they must meet labeling requirements describing their level of sun protection, as shown in Table 1.

Antibacterial skin products: Antibacterial claims can be made on products but with labeling restrictions; the product can only be presented as being active against bacteria. Labels cannot claim a product to be:

• active against viruses, fungi or other microbial organisms (other than bacteria);

• for use in connection with disease, disorders or medical conditions;

• active against a named bacterium that is known to be associated with a disease, disorder or medical condition;

• for use in connection with piercing of the skin or mucous membrane, whether for cosmetic or any other purpose;

• for use in connection with any procedure associated with the risk of transmission of disease from contact with blood or other bodily fluids;

• for use before any physical contact with any person who is accessing medical or health services, or who is undergoing any medical or health care procedure; and

• for use in connection with any procedure involving venipuncture or delivery of an injection.

Skin care anti-acne products: Products in this category, including spot treatments, cleansers, face scrubs and masks, must be labeled as controlling or preventing acne only by cleansing, moisturizing, exfoliating or drying the skin.

Oral hygiene: Products in this category include breath fresheners, toothpaste and mouth washes; the only benefits that can be claimed from using these products must be consequential to improvements on oral hygiene, including for the prevention of tooth decay or the use of fluoride for the prevention of tooth decay. Benefits must not be claimed in relation to other diseases or ailments such as gum or other oral diseases or periodontal conditions.

Hair care antidandruff products: These products must be presented as controlling or preventing dandruff only through cleansing, moisturizing, exfoliating or drying the scalp.

New Cosmetic Guidelines

Approximately one month after the Cosmetics Standard 2007 was announced, the National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS), a subset of the Australian government, issued its new Cosmetics Guidelines.4

According to NICNAS, a cosmetic is:

• a substance or preparation intended for placement in contact with any external part of the human body, including the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and the teeth, with the purpose of: altering the odors of the body; or changing its appearance; or cleansing it; or maintaining it in good condition (also see Part C of these Guidelines); or perfuming it; or protecting it; or

• a substance or preparation prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph but does not include: a therapeutic good within the meaning of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989; or a substance or preparation prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph.

In addition, the product:

• must not be intended for preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons—however, this does not preclude use of the words prevent, preventing or prevention for general cosmetic purposes;

• must not be scheduled by S2, S3 or S4, or S8 of the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons (SUSDP);

• must be marketed as a cosmetic, taking into account the labeling, packaging, advertising and/or the label statements;

• must have full ingredient disclosure in accordance with the Trade Practices (Consumer Product Information Standards) (Cosmetics) Regulations 1991; and

• may be presented as being explicitly for cosmetic purposes only. The product name would not in itself make the product a therapeutic good unless that name makes a reference to a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons.

The product must also:

• meet any applicable conditions detailed in the new Cosmetics Standard made under section 81 of the ICNA Act. The Cosmetics Standard sets the standards or conditions that apply to certain product categories. These requirements are described in Table B of Part D of these guidelines.

• not contain chemicals prohibited for use in cosmetics or that meet restrictions specified for chemicals used in cosmetics.

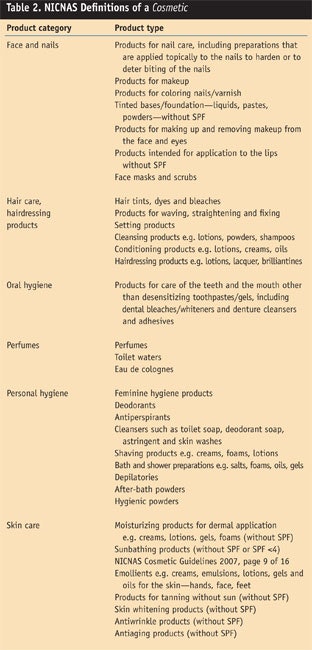

To clarify this complex definition, Australia lists the categories and types in a graphical format (see Table 2).

To further clarify these new category definitions, the following products will be yet be regulated as therapeutic goods, and not cosmetics:

• products that meet the definition of a therapeutic good in the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, including products that are for preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons

• primary sunscreens with SPF ≥ 4, as defined in AS/NZS 2604:1998

• antibacterial skin products where information is presented on the label or by other promotional means, e.g. advertising, an Internet site or point of sale material, to indicate the products: are active against viruses, fungi or other microbial organisms other than bacteria; or are to be used in connection with a specific disease, disorder or medical condition; or are active against a named bacterium that is known to be associated with a specific disease, disorder or medical condition; or are to be used in connection with piercing of the skin or mucous membrane whether for cosmetic or any other purpose; or are to be used in connection with any procedure associated with the risk of transmission of disease from contact with blood or other bodily fluids; or are to be used before any physical contact with any person who is accessing medical or health services, or who is undergoing any medical or health care procedure; or are to be used in connection with any procedure involving venipuncture or delivery of an injection

• personal lubricants.

Prohibited or Restricted Cosmetic Chemicals

Prohibited ingredients include phenylenediamines and coal tar, under the new Australian regulations, and diethylphthalate and dimethylphthalate are restricted in sunscreens, except at 0.5% or less.

Conclusions

Australia’s government has made a major step in clarifying the claims that make a product a cosmetic or a drug. It is interesting to see it has allowed lower SPF products, which are secondary sunscreens, to now be regulated as cosmetics. It is concerning how the product category designations compare with the new FDA Proposed Rules, shown in Table 3.

Clearly, the FDA’s categories give consumers more accurate information and are easier to understand than the Australian rules. The Australian categories reflect older FDA descriptions. It is likely that makeup producers in the United States that have been making SPF claims and that find the new Proposed Rules in the United States nearly impossible to follow would love what Australia has done; however, would US companies ignore the rules if they were given such an option? In the past, compliance with the FDA’s rules has been an issue since the FDA rarely took action.

Australia has a better enforcement method. Instead of writing warning letters, performing inspections or approaching the US Justice Department to seize products and close operations, Australia maintains compliance with fines, which can reach as high as US$66,000. Perhaps if the United States adopted this method, it could fully fund the FDA from fines.

Finally, the issue of prohibited ingredients must be addressed. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and even politicians in California note that the European Union (EU) has banned more than 1,400 chemicals from cosmetics, while the FDA has banned less than 10. And now, look at Australia, it has prohibited only two. Of course, more than 99% of the prohibited ingredients in Annex II in the EU have never been used in cosmetics; however, NGOs interpret this statistic as a measure of how much more advanced the EU is; one can just picture the NGOs going bananas over AUS or “Oz.”

References

1. DC Steinberg, Regulatory Review: The Proposed Amendment for Sunscreen Products in the United States, Cosm & Toil 122 12(42) (Dec 2007)

2. NICNAS Cosmetics Standard, NICNA Web site; Available at: www.nicnas.gov.au/Current_Issues/Cosmetics/Cosmetic_Standard_PDF.pdf (Accessed Dec 14, 2007)

3. SAI Global, AS/NZS 2604:1998 standards

4. NICNAS Cosmetics Guidelines, NICNA Web site; Available at: www.nicnas.gov.au/Current_Issues/Cosmetics/Cosmetic_Guidelines_PDF.pdf (Accessed Dec 14, 2007)