“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—nothing more and nothing less.”

“The question,” replied Alice, “is whether you can make words mean so many different things.”1

Combine this example taken from the classic children’s book, which plays on words and changing their meanings, with the old adage, “Don’t confuse me with facts, my mind is made up,” and it produces an end result much like that of recent political actions concerning cosmetics in North America.

Canada

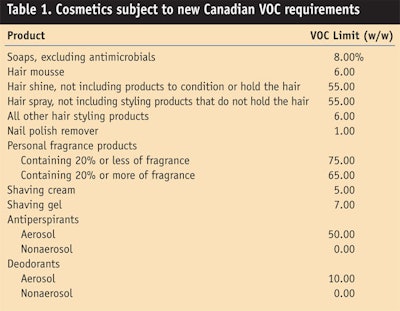

VOCs: On April 26, 2008, Canada released new Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) requirements.2 These requirements are aligned with the current California Air Resources Board (CARB) requirements in which companies that emit VOCs are required to register and maintain VOC records for five years. These must be sent to the Canadian Minister of Environment upon request. Cosmetic products subject to these new requirements are listed in Table 1.

Canada’s alignment with California and the same movement by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to adopt some of these limits will make it easy for manufacturers to justify producing only a single formulation. Although it may be easier to offer just one formulation, and the VOC limits may be better for the environment, the end result is generally poorer performing products. The largest impact is in hair sprays—the lower VOCs result in much longer drying times. Perhaps as a result, the “Twiggy” look of the late 1960s that did not require hair fixatives will be revived.

Draft screening assessment reports (SARs): Another major change came from Environment Canada concerning “Risk Management Scoping Documents.” These documents are a review of chemicals that were grandfathered into the Canadian Domestic Substance List (DSL). The first personal care chemicals reviewed were released on May 17, 2008; the first chemical for use in any industry was officially released on April 19. However, the press learned about this release on April 16 while I was in Ottawa, thus I can give a first-hand account of the public’s reaction.

The first chemical was bispenol A (BPA; INCI: 4,4’-isopropylidenediphenol; use—not reported), which is used as a starting material for polycarbonate plastics and epoxy coatings. This chemical was declared to be toxic by the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA-toxic) but is now subject to a 60-day comment period with “the intention of reducing exposure and increasing safety.” This statement could be interpreted as meaning banning its use, restricting its use or restricting how much “free” BPA can be exposed to consumers. Additional details will be published after the comment period.

The next morning on television, stores were shown pulling baby bottles made from polycarbonate plastics off of shelves. It became frenzied as consumers lined up to return bottles. When I returned to the United States from Canada, local newspaper headlines read: “Canada Declares Baby Bottles to be Toxic.” One wonders if Humpty Dumpty or Alice wrote that headline.

So I held up writing this column, to the dismay of my editor, until the first three ingredients used in cosmetics were released in order to judge the public’s reaction. These three chemicals have the INCI names: cyclotetrasiloxane, cyclopentasiloxane and cyclohexasiloxane. Some cosmetic companies use the older term cyclomethicone on their labels instead, and the industry uses shorthand to refer them as D4, D5 and D6, respectively.

Environment Canada stated these substances were identified as persistent, bioaccumulative and inherently toxic to nonhuman organisms, and believed to be in commercial use in Canada. Further, D4 was identified as a high hazard to humans with a high likelihood of exposure to individuals in Canada. Currently, there is a 60-day comment period on these materials—and unlike US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) comment periods, this will not be extended. Unless the Canadian Government is swayed from any comments sent in during this period, these materials could be subject to virtual elimination or severe restrictions.

What was interesting to me, as an observer, was the lack of public outcry or concern that accompanied the release of these chemicals, compared with BPA.

The manufacturers of these volatile silicones have submitted many studies on the safety of D4, D5 and D6. They likely have also submitted comments during this 60-day period. Since these materials did not get the same public attention, it is possible that the review by Environment Canada will be made based on science and not public opinion. However, the fear is always that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) will pick this story up and the industry will lose these ingredients to bad press.

Of course, some cosmetic company is probably already printing labels proclaiming its products to be nonvolatile silicone-free or some other destructive claim—then they turn around and complain about what is happening in California and Congress.

California

Safe cosmetic program: In 2005, the state of California passed Senate bill (SB) 484, the Safe Cosmetic Act of 2005. This required manufacturers, by Jan. 1, 2007, to submit a list of all cosmetics sold in the state that contain any ingredient the state identifies as causing cancer or reproductive toxicity. Since the state did not publish this list until Jan. 29, 2008, and has yet to create a means for manufacturers to notify the state, the industry remains in violation of this preposterous law. Should this law be null and void because the state failed to issue in a timely fashion the list by which manufacturers were expected to comply?

What is on this list? 783 chemicals. This is almost as bad as Annex II of the European Union—i.e., the banned list. Most chemicals on this list have never been used in cosmetics. Of the 1,243 chemicals prohibited in the EU, the number of materials ever used in cosmetics is less than 10. This is the so-called precautionary principle—i.e., dangerous until proven safe.

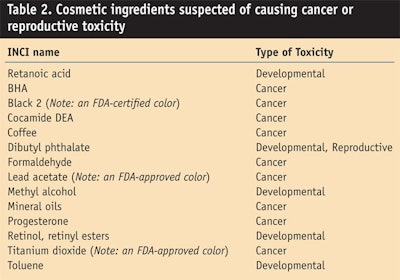

Within the California list are some surprises that could trigger unexpected notifications to the state; and remember, this list is for cosmetics, not OTC drugs. Table 2 lists ingredients that may have been used, or currently are used, in cosmetic products.

No wonder there’s such a high incidence of cancer in California. What is really scary is the inclusion of titanium dioxide, the sixth most common ingredient used in cosmetics.

To find more information on this regulation in California or to register products, visit www.dhs.ca.gov/ohb/cosmetics. Also of interest on this Web site are frequently asked questions. Here’s one worth noting:

Q: How can the California Safe Cosmetics Program benefit workers and consumers?

A: This new law requires manufacturers, packers, and/or distributors named on cosmetic product labels to provide to the California Department of Public Health a list of products that contain any chemicals known or suspected by an authoritative scientific body to cause cancer or reproductive harm. The California Safe Cosmetics Program will provide workers, employers and consumers with more information about the products they purchase and use.

If this law actually protects or benefits anyone, I would like to know. But first, rule out exposure to any of the 783 chemicals on the banned list. In fact, one day perhaps the state will notify the public of a risk of exposure to anything printed on paper since almost all paper is white due to titanium dioxide.

Migden is Back

Senator Migden, the author of the above bill, has introduced another bill to the California Senate. The new bill, SB 1712, would ban the sale of any lipstick that contains any measurable amount of lead. That means if science gets good enough to find

a single molecule of lead in lipstick, it will be banned. Such misleading science is scaring consumers. In fact, the standard for lead in drinking water is 15 ppb in the United States, and even the state of California has established a safe harbor limit of 15 µg/day for Proposition 65. So, although it is allowed in drinking water, trace amounts are not allowed in lipstick. And the real horror is that the press picks up on this “threat” and exacerbates it.

Congress

Congressman John D. Dingell represents Michigan’s 15th Congressional District and is the chairman of the Committee on Energy and Commerce in the US House of Representatives. On April 17, 2008, he issued a discussion draft of the Food and Drug Administration Globalization Act of 2008. Hearings were held May 1 and May 14 on this bill, whose primary purpose is to ensure the safety of food and drugs. In regard to cosmetics, the following issues were added:

• Mandatory registration of all cosmetic facilities—generally, any location where cosmetics are made or stored, not including retail outlets—within the United States or exporting into the United States, with a fee of US $2,000 per facility.

• Mandatory adverse effect reporting

• Mandatory good manufacturing practices

Excerpts of the actual text are as follows:

(a) In general: The secretary shall, by regulation, require that any facility engaged in the manufacturing, processing, packing or holding of cosmetics in the United States, or for import to the United States, be registered with the secretary.

(b) Application of food registration rules and registration fee: Except as provided in this section, the provisions of sections 415 and 741 shall apply to registration of cosmetic facilities under subsection (a) in the same manner as they apply to registration of facilities (as defined in section 415(b)) under such respective section except that, with respect to registration fees imposed under this subsection, any reference in section 741 to food is deemed a reference to cosmetics. Each facility shall list the cosmetic products it manufactures, processes, packs or holds in the registration and, in the case of a manufacturing facility, a list of the ingredients for each product so listed that it manufactures.

(c) Adverse event registry: The secretary shall, by regulation, require a facility that manufactures cosmetics to report to the secretary all anticipated and unanticipated serious adverse events relating to the use of cosmetics it has manufactured.

(d) Good manufacturing practices: The secretary shall, by regulation, require that the methods used in and the facilities and controls used for the manufacture, process, packing or holding of a cosmetic, conform to good manufacturing practices as prescribed in such regulations.

Effective dates—Registration and fees: Cosmetic facilities shall be required to register and pay registration fees under subsections (a) and (b) of section 604 of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, as added by subsection (a), beginning six months after the date of the enactment of this Act.

Effective dates—Adverse event registry and good manufacturing practices: The secretary of Health and Human Services shall establish the adverse event registry and the good manufacturing practices under the amendment made by subsection (a) not later than 18 months after the date of the enactment of this Act.

If Dingell’s draft passes the committee, it will probably be signed into law. The real problem will be in what it means since it is vague and subject to many different interpretations.

European Union

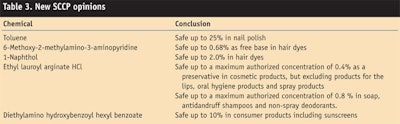

To end on a more positive note, the Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP) has issued several new opinions, summarized in Table 3. The positive opinion on toluene will enable nail polish manufacturers to continue using it, and the approval of the new preservative ethyl lauroyl arginate HCl is always welcome. These do not become part of the EU Cosmetics Directive until an Adaptation to Technical Progress is formally published.

Conclusions

It appears that the cosmetic industry is well on its way to convincing consumers that competitors’ products are not safe, while a company’s own products are touted as no longer containing unsafe ingredients—i.e., “free-from X” products. (At X, insert a favorite ingredient villain: PABA, oil, preservative, organic, chemical, etc.—maybe even titanium dioxide, now.)

No wonder California and the US Federal Government have reacted by introducing some of the toughest proposed rules in decades, and NGOs are calling for pre-approval of all cosmetics and their ingredients. How does one defend the personal care industry’s longstanding history of safety when companies declare they are no longer using unsafe ingredients? Is marketing really affixed to such self destruction? Maybe Lewis Carroll was correct.

References

1. L Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, Penguin Books Ltd.: London, UK (1995)

2. Canada Gazette, 142 17 (Apr 26, 2008)