Perfume use is as old as human history. In fact, the word perfume derives from the Latin per fumem, meaning “through smoke,” since it was customary in Antiquity to burn natural salves, herbs and oils to produce incense for religious rituals. Perfume use has been recorded in ancient Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Carthaginian, Arab and Roman civilizations. Excavations directed by Maria Rosaria Belgiorno from the Italian Archaeological Mission of the National Research Council found an ancient perfume manufacturing site in Pyrgos, Cyprus, dating back to 2000 B.C. , possibly the oldest known perfume factory found in human history. The perfume included many scents found in today’s fragrances, including rosemary, lavender, bergamot and coriander.1

Research has suggested that humans are able to retain scent recognition as far back as childhood.2 The link between humans and scent is strong, direct and emotional, and the ability of fragrance to alter or modify moods has been widely studied. In fact, some institutions have practiced piping fragrance through their ventilation systems in attempt to achieve an uplifting effect among employees.

Scientists have long established a neuronal–olfactory relationship between certain scents and colors. The perceived intensity and pleasantness of a scent is often enhanced when accompanied by an “appropriate” color associated with the particular scent.3 However, individuals perceive odors differently due to difficulties describing and communicating scents accurately. Therefore, odor classification and interpretation have been widely studied and debated. Many people use terms such as green, floral, fruity, woody, animal, spicy, sweet, musk, herbal, etc., which are further associated with certain human moods. Citrus and lavender fragrances often illicit a relaxing mood, while jasmine and peppermint are often associated as being uplifting, energizing and stimulating.4–6

Scent is also one of the key factors in shaping individuals’ conscious and/or unconscious perceptions of the environment. Savvy marketers have long known to create a pleasant service or retailing environment via strategically manipulating ambient conditions such as music, fragrance and color schemes to stimulate a more positive customer response and behavior.7,8 For instance, a 1995 study indicated that a congruent, ambient scent in a retail environment could lead to more favorable purchase decision-making, an increased amount of time spent shopping, and an extension of variety-seeking behavior.9

Another paper published in 2003 suggests that scents can be used to enhance brand memory.10 Recently, one hotel chain began piping a signature fragrance into its public spaces with a two-fold purpose, to provide a pleasant and relaxing environment to help travel-weary customers unwind, and to create a unique olfactory dimension to solidify its brand recognition.

Fragrance in Personal Care

Fragrances are a major driver in consumer purchase decision-making in an array of product categories including food and beverages, body and skin care products, household products, etc.11 As noted, fragrances often are used in personal care to affect the consumer’s perception of product performance. Most often, they add emotional benefits by implying social or economic prestige associated with use of such a product.

In 2007, Nicolas Mirzayantz listed the five major emotions associated with fragrance as: feel good, sensualism, addiction, transformation and energy. To increase the consumer’s willingness to purchase, the product must provide additional emotional cues beyond basic functionality. A consumer’s decision to make a product purchase often is based on emotional reasons that transcend his/her value systems (see Value Systems and Associated Purchasing Behaviors).12

Fragrance Chemistry

In general, fragrance ingredients are volatile, aromatic molecules of low molecular weight (< 300 mu) with low vapor pressures (< 2 mm Hg). These aromatic chemicals contain a wide range of functional groups including esters, alcohols, acetals, ketals, phenols, nitrogenous compounds, aldehydes, ketones, lactones, sulfur compounds, acids and halogen compounds. Many of these groups share a common backbone structure such as aliphatic, olefinic, terpenoid, heterocyclic and alkylaryl. These compounds can be divided roughly into 20 different scent categories, including woody, amber, musk and floral.

Not all aromatic compounds smell pleasant. The resulting pleasant fragrance is often a combination of many aromatic molecules by a perfumer skilled in the art. Most perfumes display three fairly well-known note characteristics: the top, middle and base notes. The top note contains the most volatile components of the fragrance and is responsible for the initial, immediate smell of the fragrance. The middle notes typically contain the less volatile main components of the fragrance and are responsible for the main, lasting, key aroma of the fragrance. The least volatile components make up the base note, representing the fragrance’s longest-lasting aroma.

In general, fragrances can be classified into three categories: natural, naturally derived/modified and synthetic. Natural fragrances such as florals are a complex mixture of bio-products of major plant biosynthetic pathways for phenylpropanoids, fatty acid derivatives and terpenoids. They are usually obtained from essential oils or other aromatic natural materials via physicochemical isolation.13 Naturally derived/modified fragrances include products from further chemical reactions of natural fragrances. The first synthetic aromatic compounds were developed in the 19th century, including vanillin, coumarin and salicyladehyde.14

Formulating with Fragrance

When the scent of a product is a key driver in the consumer’s purchasing decision, the formulation and the product design should allow the scent to be among the first sensory cues the consumer experiences with the product—as noted, fragrances produce emotional responses in humans, and product developers must be cognizant of the target audience.

A fragrance may lose its original aromatic characteristics when it is incorporated into non-alcoholic formulations such as emulsions. Creating a successful final scent for the finished product involves many complex aromatic chemical interactions. Experienced product formulators know to take factors into account that may affect a change in the original odor character, formulation stability and physicochemical properties of the finished formulation such as viscosity; sensitivity to pH, light and/or temperature; polarity and solubility parameters; discoloration and potential chemical interactions.

A fragrance directly from a perfume bottle or from a hydroalcoholic vehicle will not produce the same smell sensation when it is incorporated into an emulsion. Fatty compounds in the emulsion may be susceptible to rancidification, causing malodor. The addition of appropriate antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol and arylbenzofuranone compounds could be a beneficial solution to the malodor. Further, the olfactory result will not be the same after the fragrance in an emulsion is applied onto the skin. It will be affected by the individual’s skin biology including natural odor, skin micro-organisms and skin lipids.An ester-based fragrance may not be suitable for finished products requiring a low pH, since hydrolysis of esters may occur in a prolonged acidic environment.

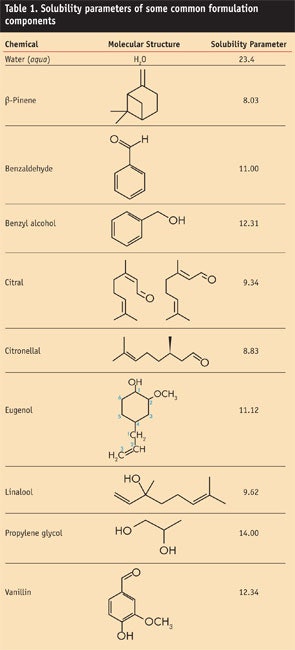

Chemical compatibility and potential interactions/reactions must be considered when introducing fragrances into antimicrobial formulations containing quaternary ammonimum compounds, oxidizing agents and strong acids or bases. Solubility parameters, the water:octanol partition coefficient and the water:dioxane partition coefficient are valuable tools to estimate the compatibility of the fragrance and other components in a formulation.15 Through careful manipulation of the partition of fragrance components within the emulsion system of various water content, a formulator can achieve better compatibility and product stability and maintain the preferred original aromatic character.16,17 Table 1 lists the solubility parameters of some common formulation components.

Safety and Regulatory Considerations

The use of fragrance in cosmetic products is regulated in the United States by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. In the EU, it is regulated through the Cosmetics Directive, and in Canada, under the Food & Drugs Act. In general, manufacturers of personal care products that incorporate fragrances must substantiate the safety of their ingredients and products. In addition, they must adhere to any specific restrictions or rules regarding prohibited uses imposed on certain fragrance components.

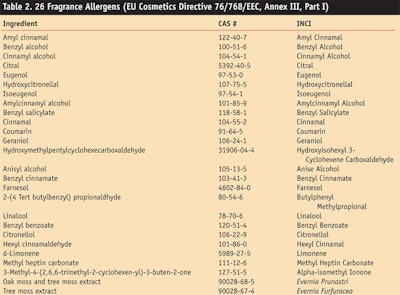

The potential to cause dermal sensitization in humans has been central to safety and regulatory concerns for the use of fragrances in cosmetic products. In 1999, The Scientific Committee on Cosmetic Products and Non-Food Products Intended for Consumers (SCCNFP) in the EU issued an opinion concerning fragrance allergy in consumers, identifying the most frequently reported and consumer-recognized fragrance allergens. Among them are amyl cinnamal, benzyl alcohol, citral and eugenol. Table 2 lists the 26 fragrance allergens as listed in the EU Cosmetics Directive 76/768/EEC, Annex III, Part I.

Allergen testing is conducted by physicians and employs various methods including a skin prick test, an intradermal skin test, and skin patch testing. These tests mostly are employed to diagnose reactions to substances such as food, venom and drugs (i.e., penicillin); asthma and rhinitis due to mold, pollen and other allergens; and allergic contact dermatitis. Patch testing is most commonly used to identify the causes of contact dermatitis but since each patient exhibits various responses to environmental allergens, there are no absolute allergen reference standards.

Many routes of exposure to fragrances exist in everyday life. Although skin contact is the most common, ingestion via flavoring agents and inhalation are also quite common. The calculation of risk must consider reasonable and pragmatic human behavior patterns.

According to the SCCNFP, a total ban of all known allergens would not be necessary to control skin allergies. Further, a total ban would significantly reduce the commercial use of plant and herbal extracts in cosmetic products. Instead, the recommendation was to properly identify and label these allergens and impose safe level use limits.

Maximum use levels were reviewed by the SCCNFP and later introduced into the Cosmetics Directive via a Technical Adaptation. The SCCNFP further indicated that labelling all fragrance ingredients on cosmetic packages would not be feasible since a fragrance can easily contain more than 100 different components. To protect the vast majority of pre-sensitized consumers, the SCCNFP thus recommended imposing the cut-off levels to avoid excessive labelling. For rinse-off products, the maximum allowed is 0.01% (100 PPM) and for leave-on products, 0.001%

(10 PPM).

In addition to official regulations and laws regulating fragrance in cosmetics, there are several self-regulating programs established through the International Fragrance Association (IFRA), which establishes such practices for the fragrance industry worldwide, including the industry’s code of practice and safety standards.

The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) is a nonprofit corporation that was formed in 1966 to gather and analyze scientific data, engage in testing and evaluation, distribute information, cooperate with official agencies, and encourage uniform safety standards related to the use of fragrance ingredients. RIFM maintains the largest database of flavor and fragrance materials worldwide (4500+ materials), with an online collection of Flavor/Fragrance Ingredient Data Sheets (FFIDS).

FFIDS are issued to assist with compliance of the Occupational, Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Hazard Communication Standards in the United States, and the European Commission’s Dangerous Substances Directives. RIFM receives advice from an independent panel of experts, the RIFM Expert Panel (REXPAN), an international group of dermatologists, pathologists, environmental scientists and toxicologists, to set its strategic direction, review protocols and evaluate scientific data. IFRA relies on REXPAN’s conclusions as its basis for setting fragrance standards.

A group of international experts including the COLIPA Toxicology Advisory Group and the Joint COLIPA/AISE/EFFA/IFRA Perfume Safety Group convene regularly to address dermal sensitization risk assessment for fragrance ingredients. These groups collaborate as a part of ongoing research by IFRA and RIFM, and jointly present lectures and publish newsletters and conference proceedings, etc. The group issued a technical dossier on the Dermal Sensitization Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) for Fragrance Ingredients in 2006, recommending an exposure-based QRA methodology for fragrance ingredients.18 Some key conclusions include:

- to evaluate a potential fragrance skin sensitizer, a Weight of Evidence (WOE) approach to determine a No Expected Sensitization Induction Level (NESIL);

- sensitization assessment factors (SAF) based on published peer-reviewed scientific data;

- predefined SAF for product types;

- expression of the NESIL and Consumer Exposure Level (CEL) in dose per unit area; and

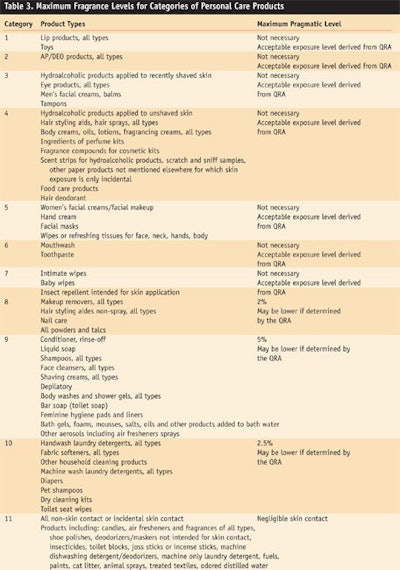

- the use of QRA for fragrance ingredients to establish IFRA standards with improved product category classification. The previous system included only two product categories (skin contact and non-skin contact products) for dermal sensitization concerns, which has been replaced by a new classification standard including 11 categories with defined maximum pragmatic levels of fragrance usage (see Table 3).

Natural and Sustainable

Arylessence Inc. recently presented 14 trends for 2009 in a report19 in which perfumers describe fragrance notes that reflect each trend and suggest how products can be shaped by the various scent and fragrance themes.20 These trends point to a common observation that consumers are not only interested in their own well-being, but also want to show deep respect for the environment.

Motivated by the global green chemistry movement, many consumer advocacy nongovernmental organizations (NGO) have attempted to champion the safety of cosmetic products as well as concerns beyond safety and quality. The overwhelming global acceptance for replacing animal testing for cosmetic products is but one of these many green initiatives. Other issues looming on the horizon concern the use of fragrances in personal care, including regional regulations such as California’s Safe Cosmetics Act; personal care product VOCs restrictions for indoor air pollution control; competing product standards for natural and/or organic certification; global sustainable sourcing and fair trade practices; cosmetic product and ingredient quality; and safety and counterfeiting challenges.

The REACH Regulation, enacted on June 1, 2007, is an example of how legislation can make an impact on how the world conducts chemical business. This legislation is based on the precautionary principle and provides a single integrated chemical regulatory scheme for all EU member states. It is designed to ensure a high level of protection of human health and the environment by requiring the industry to provide data for safety and risk assessment. Unless a material is exempt, the regulation imposes a strict “no data, no market” rule over all chemical substances. Any substance imported or manufactured in the EU in volumes over 1 tonne per year requires registration with the European Chemicals Agency.

Although finished cosmetic products are exempt from REACH registration requirements, the individual ingredients are not, unless specifically exempt. One exemption that potentially benefits the fragrance industry is the Annex V (Naturally Occurring) Exemption. This exemption is for aromatic plant extracts and botanicals that meet the defition of “occurring in nature.”

The International Standard for Sustainable Wild Collection of Medicinal & Aromatic Plants (ISSC-MAP)21 is a green sourcing practice standard developed in 2007 as a joint effort of many organizations including the World Conservation Union, Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN), MPSG/SSC/IUCN, WWF Germany and TRAFFIC (the Wildlife Trade Monitoring Network). It was designed to assist those involved in the harvest, management, trade, manufacture and sale of wild-collected MAP resources to understand and comply with the conditions under which sustainable collection of these resources can take place. Other global and regional fair trade organizations include the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development BioTrade Program (the Union for Ethical Biotrade), established in 1996, and Phytotrade Africa, which joins eight South African nations to develop a regional fair trade and environmentally sustainable natural products industry.

In this global quest for an eco-friendly future, old foes are becoming new allies. One could expect to see an even higher level of cooperation between regulatory authorities, industrial private sectors, environmental NGOs and academia.

Conclusions

A multidimensional approach must be taken to successfully design scented products not only with compatible components, but that also provide a positive consumer experience. To reach the targeted market, formulators must tie together sensory cues, including scent classification, olfactory-visual effect, scent presentation over time—i.e., the distribution and dissipation from the top notes to the base notes—and user mood. By sustaining the most preferred note of a fragrance, the consumer’s shopping experience can be enhanced, which can lead to a future purchase and reinforce brand recognition. Product formulators must also consider the interaction of the formula with the packaging material and under various environmental conditions.

Product formulators must take all these factors into account while remaining cognizant of fragrance material regulations. Formulating a scented product is not just incorporating a scent; there is more to it than meets the nose.

References

1. P Caffarelli, The perfumes of Aphrodite and the secret of oil, Archaeological discoveries on Cyprus Exhibition, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Mar 14–Sept 2, 2007

2. WP Goldman and JG Seamon, Very long-term memory of odors: retention of odor-name associations, Amer J of Psych 105(4) 549–63

3. RA Osterbauer, PM Matthews, M Jenkinson, CF Beckmann, PC Hansen and GA Calvert, Color of Scents: Chromatic stimuli modulate odor responses in the human brain, J Neurophysiol 93 3434–3441 (2005)

4. IFF, Fragrance evaluation techniques for individuals looking to evaluate fragrances, prepared for Colgate Palmolive, Australia (2002)

5. JS Jellinek, Perfume classification: A new approach, Chapter 15 in The Psychology and Biology of Perfume, Barking, Essex, UK: Elsevier Science Publishers (1991)

6. H Ehrlichman and L Bastone, The use of odour in the study of emotion, Chapter 10 in Fragrance: The Psychology and Biology of Perfume, Barking, Essex, UK: Elsevier Science Publishers (1992)

7. LW Turley and JC Chebat, Linking retail strategy, atmospheric design and shopping behavior, J of Marketing Management 18:125 (2002)

8. LW Turley and DL Bolton, Measuring the affective evaluations of retail service environments, J Professional Services Marketing 19, 31 (1999)

9. DJ Mitchell, BE Kahn and SC Knasko, There’s something in the air: Effects of congruent or incongruent ambient odor on consumer decision-making, J Consumer Research 22(2) 229–38 (1995)

10. M Morrin and S Ratneshwar, Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? J Marketing Research 40(1) 10–25 (2003)

11. O Wolfe and B Busch, Two cultures meet and create a third: From consumer goods and fine fragrances to new product concepts, Seminar on Fine Fragrances and Fragrances in Consumer Products Using Research and Development and Optimisation, London, E.S.O.M.A.R., Amsterdam (Nov 13–15, 1991)

12. NA Mirzayantz, Vision for the Future, presentation at Fragrance Business 2007, HBA Global Expo, New York City (Sept 19, 2007)

13. I Guterman et al, Rose scent: Genomics approach to discovering novel floral fragrance-related genes, The Plant Cell 14 2325–2338 (2002)

14. G Frater, JA Bajgrowicz and P Kraft, Tetrahedron 54 7633–7703 (1998)

15. TrendWatch 2009, Arylessence (June 20, 2008) http://www.gcimagazine.com/marketstrends/consumers/20599289.html (Accessed Sept 17, 2009)

16. S Herman, Fragrance in emulsion and surfactant systems, Cosm & Toil 121(4) 59–67 (2006)

17. F Buccellato, The Art & Science of Fragrance in Functional Products, Cosm & Toil 99(4) 41–43 (1984)

18. SJ Herman, Fragrance chemistry: The art and the science, Chemtech, 8, 458–462 (1992)

19. QRA Expert Group, Dermal Sensitization Quantitative Ris Assessment (QRA) for Fragrance Ingredients, Technical Dossier, issued Mar 15, 2006, revised May 26, 2006

20. Fragrance and Color Inspire 2009 Trend-Watch(R) Report: New resource for Defining Fragrance Trends, Jun 17, 2008, Reuters, www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS80350+17-Jun-2008+PRN20080617 (Accessed Sept 17, 2009)

21. Medicinal Plant Specialist Group, Species Survival Commission, IUCN the World Conservation Union. International Standard for Sustainable Wild Collection of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (ISSC-MAP), Version 1.0., 2007, www.floraweb.de/map-pro/Standard_Version1_0.pdf (Accessed Sept 17, 2009)