Hair loss, a common affliction of humans, occurs in many pathophysiological conditions of the skin as well as in systemic disorders. Classification of hair loss is commonly divided into two categories: Cicatricial and non-cicatricial alopecia. Cicatricial alopecia results from hair follicle damage complicated by various pathological changes of the surrounding skin. Non-cicatricial alopecia is caused either by functional or structural disorders of the hair follicle itself.

Male pattern alopecia, also called androgenetic alopecia or AGA, is the most common non-cicatricial hair loss affliction.1 It becomes a major therapeutic challenge for dermatologists due its refractory and mostly irreversible characteristics. Indeed, all causes and pathogenetic backgrounds of androgenetic alopecia are largely unknown, although some research has shown the deregulation of two major hair follicle cell types are involved in this pathology: Human fibroblast dermal papilla cells (HFDPc) and outer root sheath cells (ORSc).

In AGA, androgens deregulate HFDPc-secreted factors involved in normal hair follicle cell differentiation via the inhibition of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.2 Based on this finding, the current authors focused their work on the roles of these two cell types in the hair follicle morphogenesis cycle.3

This article describes tests to assess the in vitro capabilities of an active ingredient composed of dihydroquercetin glucoside and epigallocatechin glucoside to stimulate ORSc and HFDPc to reverse AGA. Dihydroquercetin had previously shown novel properties for hair growth, as will be discussed, but its glycoside had not previously been tested. The effects and capabilities of this blend were tested in vitro on the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and on cell metabolism and proliferation. The capability of the blend to induce AGA hair follicle growth also was determined ex vivo and in a clinical study.

Test Compounds

The test blenda consisted of: a sterile solution of dihydroquercetin glucoside (DHQC) between 4.44 and 5.62 mM; in association with epigallocatechin gallate glucoside (EGCG2), 0.4 to 0.605 mM, in water with glycine, 21.8 to 27.2 mM; and zinc chloride, 4.97 to 7.02 mM. This blend will be referred to as DEGZ hereafter. DEGZ was used either at 0.001% or 0.1% for in vitro studies; 1% for the ex vivo study; or 3% for clinical studies.

In vitro Cell Cultures

Viability and proliferation tests were performed on normal human ORS cellsb and on normal human HFDP cells seeded at 10,000 cells/cm2. ORSc were incubated for 24 hr and HFDPc were incubated for 48 hr with increasing amounts of DHQG of 2 μM, 10 μM and 50 μM. The following positive controls were used: β-FGF at 10 ng/mL for HFDPcd and EGF at 10 ng/mL for ORSce.

In vitro HFDPc Viability

A cell viability assay was carried out using the XTT reagent 2,3-Bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide, a yellow tetrazolium solution that is cleaved to a soluble orange formazan dye in the mitochondria of metabolically active cells. In actively proliferating cells, an increase in XTT conversion is quantified. Conversely, in cells that are undergoing apoptosis, XTT reduction decreases, reflecting the loss of cell viability.

After treatments with DHQG or the controls, cells were incubated with XTT at 0.25 mg/mL for 3 hr, following which the optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader. Wells without cells were used as blanks. Each condition was performed in triplicate. Morphological observations of cells were made under a microscope.

Cell viability results were expressed as a percentage in comparison with the untreated group. Statistical analysis was performed using the student’s t-test with the following threshold: significant difference at 99% if p < 0.01* and at 99.9% if p < 0.001**.

In vitro ORSc Proliferation

To assess cell proliferation, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) diluted at 1/100 was incorporated in the culture media during the last 16 hr of DHQG treatment. After staining, optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader. For proper data management, the OD read was corrected using the blank value. The results of cell proliferation were expressed as a percentage in comparison with the untreated group. Statistical analysis was performed using the student’s t-test with the following threshold: significant difference at 99% if p < 0.01*.

In vitro Western Blot Analysis

ORSc from the occipital hair follicles of three AGA donors were seeded on collagen I-coated 6-well plates (2000 x 105 cells per well) and allowed to adhere for 24–48 hr. ORSc were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium (KSFM)f containing 0.25% v/v BPEf, 0.2 ng/mL epidermal growth factorf, 300 μM calcium chlorideg, 100 units/mL penicillinh and 100 mg/ mL streptomycinh.

Once normal keratinocyte morphology was observed, tests were carried out with cell culture-grade water vehicle (control)f or with the DEGZ blend diluted at 0.001%, 0.01% and 0.1%, respectively containing the following amounts of EGCG2/DHQG: 0.005/0.05 μM, 0.05/0.5 μM and 0.5/5 μM. ORSc were treated for 24 hr, then washed in ice cold PBSg and lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing 50 mM tris-HCl pH 7.4g; 150 mM NaClg; 0.25% Na-deoxycholateg; 1 mM EDTAg and protease inhibitor tabletj.

Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4˚C and then the supernatant was extracted and quantified for total protein using a detergent-compatible quantification kitk. Lysates were adjusted according to their total protein concentration using RIPA buffer, then Western blot analysis was carried outm. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and stained with a 1:1000 dilution of non-phospho beta-cateninp or a 1:10,000 dilution of β-tubulin loading controlq.

In vitro Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis analysis was carried out using Guava Nexin reagent in conjunction with a flow cytometer according to the manufacturer’s instructionsr. Briefly, ORSc were treated with DEGZ diluted at 0.001%, 0.01% and 0.1% or vehicle control for 24 hr, then trypsinized using EDTA solutions. ORSc were countedt and centrifuged for 5 min at 900 rpm, then resuspended in DMEM mediaf containing 10% fetal bovine serumu to a volume of 50,000 cells per mL.

The cell suspension was then mixed with an equal volume of Guava Nexin reagent and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 20 min. Vials of the cell suspension were then measured using flow cytometryr.

Ex vivo Follicle Cultures

For ex vivo tests, hair follicles were extracted from the occipital scalps of AGA donors. Thirty follicles each were isolated from two donors. At this stage, it was not possible to identify follicles in the anagen phase; however, only follicles in the anagen phase should be included for the growth study. Identification of hair follicles in the anagen phase was therefore performed after culture by following only growing hair follicles.

For three test groups, i.e., DEGZ, minoxidil and untreated, respectively 10, seven and seven hair follicles identified as in the anagen phase were selected.

These individual follicles were cultured according to the Philpott model. Each isolated follicle was immediately placed into one well of a 24-well plate containing a specific medium. This medium consisted of Williams' medium E, L-glutamine, insulin, hydrocortisone, penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The medium with or without the test product was replaced every day.

The growth of hair follicles was examined at D7 and D10 using a digital microscope at a magnification of 40× and was followed using the microscope and image analysis software. The length in μm of each hair follicle was measured from digital images at D0, D7 and D10.

To ensure proper data management, raw data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel software. All reported data was expressed as mean ± SEM (μm). The standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated as the standard deviation (SD) divided by the square root of sample size; thus, standard error of the mean: SEM = SD/√n. Inter- and intra-group comparisons according to time were performed by the student’s t-test. The significance was judged as follows: significant difference at 95% if p < 0.05* and at 99.9% if p < 0.001**.

The presented data is consistent with previously published data showing the role of EGCG in the stimulation of HFDPc and hair follicle growth.

Clinical Study Protocol

The aim of the clinical investigation was to evaluate the effectiveness of the DEGZ blend at 3% to treat AGA. A test lotion was developed consisting of: water (aqua), alcohol denat., butylene glycol, glycerin, xanthan gum, disodium EDTA and citric acid; with or without 3% of the DEGZ blend (150 μM DHQG/15 μM EGCG2).

Regarding the test panel and parameters, 26 male volunteers having a hair loss grade III to IV on the Hamilton scale amended by Norwood were included in a randomized and double-blinded study. Volunteers were between the ages of 18 and 70 years old, and of Caucasian or North African descent. Each volunteer had a minimum of 40 telogen hairs/cm2 and a minimum density higher than 150/cm2.

Each volunteer applied a 3.5-mL sample of test hair lotion to the scalp daily for 84 days with no rinsing after application. In total, 14 volunteers tested the 3% DEGZ formula while the remaining 12 tested the placebo.

Phototrichogram Assessments

All clinical observations were performed under the control of a dermatologist. Hair parameters, described next, were assessed before (D0) and after one and three months of hair lotion application. Phototrichograms (PTGs) were used to non-invasively and accurately measure hair. Images were acquired of specified areas of interest using standardized and reproducible conditions for distance, light and zoom by a reflex camerav associated with a specified flash system and contact plane having a graduated straight edge. Images were taken at D0, D28 and D84, and two days after each of these dates—i.e., D2, D30 and D86. Scalp pictures also were taken before and after treatment under standardized conditions.

PTGs were taken of one 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm area. Hairs were cut with scissors, then shaved from the root with a hair clipper. Photos were taken for each kinetic. For each picture, the reference picture for the position was the original captured upon screening, Day 0. Image analysis was carried out using softwarew.

Hairs were counted in a 0.7-cm² area and distinguished by their growing phase as different colors. Three hair categories were defined: hair in anagen phase (A); hair in telogen phase (T); and "undetermined" hair (I)—i.e., hairs for which the growing phase was difficult to evaluate.

The pillar formulas utilized are described in the sidebar, Phototrichogram Calculations.

These parameters were selected because the hair loss process directly impacts them. In alopecia, the percentage of hair in the telogen phase increases with time, whereas the percentage of hair in the anagen phase continues to decrease.

To ensure proper data management, raw data was analyzed with Microsoft Excel software. All reported data was expressed as mean ± SEM and absolute variations. The standard error of the mean (SEM), again, was calculated as the standard deviation (SD) divided by the square root of sample size—i.e., standard error of the mean: SEM = SD/√n. Intra-group comparisons according to the time were performed by the student’s t-test. Differences were judged as significant at 95% if p < 0.05* and at 99% if p < 0.01**.

Results: HFDPc Viability and ORSc Proliferation

As noted, in vitro cell viability assays were carried out using XTT to assess the effects of DHQG on HFDPc viability over a range of concentrations. Figure 1 shows the viability was slightly but significantly (p < 0.01) stimulated by DHQG treatment. The improvement in HFDPc viability was +12%, +16% and +24% at 2 μM, 10 μM, and 50 μM DHQG, respectively, and compared with a 20% (p < 0.01) increase in HFDPc maintained with 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, which served as the positive control.

In addition to DHQG on HDPFc viability, the effects of DHQG on human hair follicle-derived ORSc proliferation were assessed. Figure 2 shows that DHQG significantly (p < 0.001) stimulated ORSc proliferation over a range of concentrations; +28%, +40% and +44% respectively at 2 μM, 10 μM and 50 μM of DHQG. It is also worth noting that DHQG stimulated higher rates of cell proliferation than 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (+14%, p < 0.01). This data is consistent with that of Keisuke et al., who showed, using mouse hair epithelial cells, that the non-glucosylated form of DHQG (taxifolin, 10 μM) had proliferative properties.4

Results:Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

Due to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway being inactive in AGA hair follicle cells, the authors investigated whether DEGZ could activate this pathway via the induction of β-catenin nuclear translocation.2 For this assessment, the western blot technique was used. The data demonstrated that DEGZ diluted at 0.1% exhibited a marked activation of β-catenin in ORSc (see Figure 3). Interestingly, this effect happened without cross-talk between ORSc and HFDPc.

During hair cycle morphogenesis, this cross-talk is crucial for the initiation of new anagen hair follicles.5 Indeed, soluble factors from human hair papilla cells (HFDPc) induced an increase in the clonal growth of outer root sheath cells, and their differentiation into hair matrix cells by activation of this pathway.6

Results: Apoptosis Assay

DEGZ diluted at 0.1% also demonstrated an anti-apoptotic effect on ORSc (see Figure 4), which is most probably due to a synergistic effect of DHQG and EGCG2. Kwon et al. have shown, on HFDPc, that the non-glycosylated form of EGCG2, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), from 0.01 μM to 0.5 μM has anti-apoptotic properties.7 This property was also confirmed by Park et al. on human dental pulp cells.8

In AGA pathology, the premature termination of anagen is associated with premature entry into catagen an apoptotic-driven process. The catagen phase of the hair cycle occurs due to decreased expression of anagen-maintaining factors such as growth factors IGF-1, β-FGF and VEGF, and an increased expression of cytokines (TGFβ 1, IL -1α and TNFα), which promotes apoptosis.1

The anti-apoptotic properties of the two molecules, DHQG and EGCG2, could therefore delay the entrance of hair follicles in the catagen phase of hair cycle. The anti-inflammatory properties of EGCG2 (data not shown) may also help to delay entry into the catagen phase.

Results: Ex vivo

AGA hair follicles treated with 1% DEGZ (50 μM DHQG/5 μM EGCG2) grew faster than untreated hair follicles or follicles treated with minoxidil after seven or 10 days (see Figure 5). In comparison with untreated controls, the growth rate was increased significantly (p < 0.001**) by +75% after seven days and +214% after 10 days of treatment with the test blend.

In comparison with the untreated control, the growth increased by +25% (insignificant) after seven days and +118% (significant at p < 0.05*) after 10 days of treatment with minoxidil. In the present study, the results obtained after minoxidil treatment were lower than those described in literature. In fact, the ex vivo model demonstrated minoxidil imparted limited effects on AGA hair follicle growth. Minoxidil results in this ex vivo model were also dependent on the rigorous selection of hair follicles (i.e., occipital or frontal hair follicles) and on their stages in hair cycle (anagen VI was strictly required).9

It also has been shown in ex vivo culture models that minoxidil does not significantly increase hair shaft elongation, especially in hair follicles from occipital area.10 In the present study, no selection of anagen VI hair follicles was made and the hair follicles were from the occipital region.

Hair follicle growth also was studied after daily treatment of the hair follicle by a mix containing 10× lower the amount of EGCG2, then cultured during seven and 10 days (data not shown). This study showed no growth stimulation, demonstrating that EGCG2 is important to achieve hair growth.

Taken together, the presented data is consistent with previously published data showing the role of EGCG in the stimulation of proliferation of dermal papilla fibroblasts (HFDPc) and the promotion of human hair follicle growth.7 Even DHQG, which is very potent on the cellular level, shows synergistic action with EGCG2, to deliver its full activity in the hair growth follicle stimulatory process.

AGA hair follicles treated with 1% DEGZ grew faster than untreated hair follicles or follicles treated with minoxidil after seven or 10 days.

Results: Clinical Studies

It is well-known that the growth of scalp hair is a cyclical process, made up of successive phases of growth (anagen) and rest (telogen).11, 20 In a non-balding scalp, more than 90% of scalp hair is in an anagen phase.12

However, with AGA, the progressive shortening of the anagen phase, as well as an increase in the duration of the lag phase (i.e., the interval between the shedding of a telogen hair and the emergence of a replacement anagen hair), across successive hair cycles, progressively decreases the percentage of hair follicles in the anagen phase. For men with male pattern hair loss, only 60% to 80% of total hairs are in anagen phase. This shortening of the anagen phase leads to progressive miniaturization of hair follicles, which contributes to a decrease of visible hair over affected areas of the scalp.13

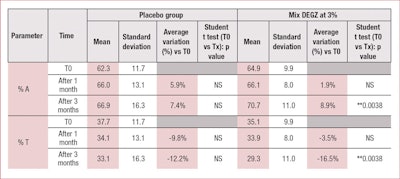

In the present clinical study, the authors demonstrated that treatment with DEGZ 3% for three months daily efficiently treats androgenetic alopecia by increasing the percentage of hair in the anagen phase (by about +9%) and decreasing the percentage of hair in telogen phase (by about -17%) (see Table 1). In this study, an insignificant placebo effect also was observed, likely due to the mechanical activation of microcirculation, with almost no more evolution after one month.

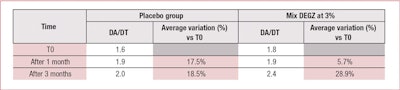

None of the results obtained with the placebo were statistically significant. However, 3% DEGZ increased the density ratio of hair in the anagen phase to hair in the telogen phase. After three months, the ratio reached 2.37 (+29%) while the placebo showed no evolution after one month (see Table 2). Furthermore, this hair density increase observed after three months of treatment was confirmed by the scalp’s macrophotography (see Figure 6).

At the end of the study, volunteers using the test DEGZ formula judged their hair as stronger and thicker (data not shown). These benefits are likely provided by the glycine and zinc in the test blend. Glycine is an essential component for the hair shaft structure that directly enters hair’s composition of keratin-associated protein.14 Zinc reinforces hair shaft structure and is essential for cystin incorporation into keratin.15

Conclusion

DHQG and EGCG2 are two glucosylated derivatives of native dihydroquercetin and epigallocatechin gallate. These two polyphenols were previously shown to have different properties for hair care.7, 16

The present studies demonstrate that when these two molecules are used alone or in combination, beneficial properties are observed; including HFDPc metabolism stimulation, ORSc proliferation, beta catenin activation and anti-apoptotic effects on ORSc. In combination with EGCG2, and glycine and zinc, DHQG also induced the growth of AGA hair follicle explants cultured in vitro according to the Philpott model. This study also confirmed the crucial role of EGCG2 in hair growth induction.

Clinical investigations described here show this blend can treat androgenic alopecia by re-launching hair growth pathways and visibly decreasing hair loss within three months by promoting the conversion of hair follicles into the anagen phase via the activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and by limiting the apoptosis of ORSc. Finally, the efficiency of the test blend as an alopecia hair loss treatment was confirmed by a high user satisfaction rate (+71%) during the clinical investigation.

References

- F Kaliyadan, A Nambiar and S Vijayaraghavan, Androgenetic alopecia: An update, Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 79(5) 613-25 (2013)

- GJ Leiros, AI Attorresi and ME Balana, Hair follicle stem cell differentiation is inhibited through cross-talk between Wnt/beta-catenin and androgen signalling in dermal papilla cells from patients with androgenetic alopecia, Br J Dermatol 166(5) 1035-42 (2012)

- TS Purba et al, Human epithelial hair follicle stem cells and their progeny: Current state of knowledge, the widening gap in translational research and future challenges, Bioessays 36(5) 513-25 (2014)

- T Keisuke, Polyphenols from the heartwood of Cercidiphyllum japonicum and their effects on proliferation of mouse hair epithelial cells, Planta Med (2002)

- C Roh, Q Tao and S Lyle, Dermal papilla-induced hair differentiation of adult epithelial stem cells from human skin, Physiol Genomics 19(2) 207-17 (2004)

- A Limat et al, Soluble factors from human hair papilla cells and dermal fibroblasts dramatically increase the clonal growth of outer root sheath cells, Arch Dermatol Res 285(4) 205-10 (1993)

- OS Kwon et al, Human hair growth enhancement in vitro by green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), Phytomedicine 14(7-8) 551-5 (2007)

- SY Park et al, Epigallocatechin gallate protects against nitric oxide-induced apoptosis via scavenging ROS and modulating the Bcl-2 family in human dental pulp cells, J Toxicol Sci 38(3) 371-8 (2013)

- OS Kwon et al, Human hair growth ex vivo is correlated with in vivo hair growth: Selective categorization of hair follicles for more reliable hair follicle organ culture, Arch Dermatol Res 297(8) 367-71 (2006)

- M Magerl, Limitations of human occipital scalp hair follicle organ culture for studying the effects of minoxidil as a hair growth enhancer, Exp Dermatol 13(10) 635-42 (2004)

- G Cotsarellis, Gene expression profiling gets to the root of human hair follicle stem cells, J Clin Invest 116(1) 19-22 (2006)

- DJ Van Neste, B De Brouwer and W De Coster, The phototrichrogram: Analysis of some technical factors of variation, Skin Pharmacol 7(1-2) 67-72 (1994)

- M Courtois et al, Hair cycle and alopecia, Skin Pharmacol 7 (1-2) 84-9 (1994)

- GE Rogers, Hair follicle differentiation and regulation, Int J Dev Biol 48 (2-3) 163-70 (2004)

- JM Hsu and WL Anthony, Impairment of cystine-35S incorporation into skin protein by zinc-deficient rats, J Nutr 101(4) 445-52 (1971)

- VS Shubina and YV Shatalin, The effect of the liposomal form of flavonoid-metal complexes on skin regeneration after chemical burn, Cell and Tissue Biology 6(4) 396-406 (2012)