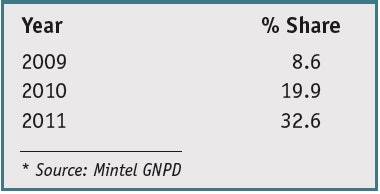

White and fair skin are viewed as symbols of beauty by Chinese, Japanese and Koreans for geographical, racial, cultural and traditional reasons. In China, there is an old saying that, “A white complexion is powerful enough to conceal thousands of faults.” Observing the Chinese cosmetic market today shows that products with skin-whitening claims are the most popular. In fact, according to AC Nielsen data, whitening products make up nearly 30% of the total skin care market in China.1 The market for such products continues to grow at a fast rate. For example, the sales value of whitening facial cream increased 17.9% and 6.2% year-on-year in 2010 and 2011, respectively (see Table 1). Consequently, skin whitening has become one of the hottest areas of focus among R&D in Chinese cosmetic enterprises.

Meanwhile, statistics have shown that products with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) claims account for a large share of the skin-whitening product market in China—nearly 33% in 2011, which has risen year after year (see Table 2). This article thus serves as a summary of the historic and current application of TCM in whitening cosmetics. It also provides a preliminary discussion of the challenges faced when incorporating TCM into skin care and skin-whitening products.

Historic Use of TCM in Skin Whitening

Approximately 1,974 prescriptions are recorded in more than 38 historic medical references from the Eastern Jin Dynasty (AD 317–420) through the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644–1911) of China. Of these prescriptions, 465 are related to skin whitening or lightening, accounting for nearly a quarter of the total.2 Further, research by scholars on the medical monographs Qian Jin Fang found there are 15 kinds of TCM usually applied in skin whitening,3 of which the skin whitening effects have been proven by modern scientific research.4 These include: Angelica dahurica, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz., Ampelopsis japonica (Thunb.) Makino, Aconitum coreanum (Levl.) Raipaics, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Vigna cylindrica Skeels, Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vaillant, Santalum album L., Gallus domesticus Brisson and Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn. This indicates that China has a long history of using TCM to solve the problem of skin whitening, and there is scientific evidence of its efficacy.

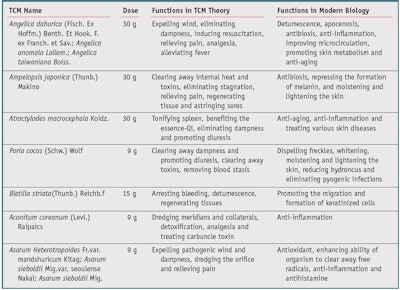

A recipe using seven whitening herbs called “Qi Bai Gao”—literally “Seven White Ointment,” (see Table 3) is one of the most famous skin whitening or skin care formulae recorded in existing ancient Chinese medical classics. It is named after the first Chinese characters of the six TCM ingredients used in the formula that begin with the Chinese character Bai, and the last Chinese character of Gallus domesticus Brisson, which is also Bai. This formula was recorded in the book Yu Yao Yuan Fang5 as a prescription to treat freckles and whiten facial skin. Based on royal prescriptions of the Song, Jin and Yuan Dynasties, this book was the first to compile more than 1,000 royal medical prescriptions made available to commoners, and it was block-printed in AD 1257. A large portion of the prescriptions in the book relate to human health and beauty and are as authoritative as they were originally for royal use.

Practically, the manufacturing process of Qi Bai Gao is as follows: peel the root of Poria cocos (Schw.) wolf and use raw Aconitum coreanum (Levl.) Raipaics. Remove the leaves and soils of Asarum Heterotropoides Fr.var.mandshuricum Kitag and grind all the herbal ingredients in the formula together until they become fine powder. Reconcile the powder with Gallus domesticus Brisson, i.e., egg white, and make sticklike objects, called “Tingzi,” similar to a human’s little finger in size. Dry the Tingzi in shade and put them in storage afterward.

The application procedure is: Grind the Tingzi with tepid rice water, i.e., the water drained after rinsing the rice, until pulp juice is obtained. Following facial cleansing each night, apply the juice onto the face before sleep. It is noteworthy that the proportions of each TCM ingredient in Chinese classic prescriptions are not unchangeable. The fact is that in ancient China, where cosmetics were not yet industrially produced on a large scale and their commercialization rates were extremely low, prescriptions were individualized based on doctors’ judgments most of the time. Factors taken into consideration included the individual’s health condition and lifestyle, and seasons as well as the natural environment when and where the preparation is applied. The increase or decrease in dose differs from individual to individual. In this sense, the so-called formulae recorded in Chinese medical classics such as the Qi Bai Gao can only be considered as the basis for general types of prescriptions.

According to recent research of the original Qi Bai Gao, the underlying TCM theory and philosophy are as follows.12 Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. serves as the “monarch,” i.e., plays the most important role in the formula, and is responsible for treating a dull complexion or colored patches. Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf is considered the “minister” in the formula, helping to maximize the monarch’s skin-whitening efficacy. Angelica dahurica, Asarum Heterotropoides Fr.var.mandshuricum Kitag, Bletilla striata (Thunb.) Reichb.f and Ampelopsis japonica (Thunb.) Makino, on the other hand, are “assistants” to the monarch and minister in the formula, functioning together to astringe sores and regenerate tissues. Aconitum coreanum (Levl.) Raipaics, which helps treat various facial diseases and strengthens the treatment efficacy of other TCM ingredients, serves as the “guide.” The “guide” helps the monarch, minister and assistant to arrive at the target organs and mediate the medicinal properties. Here, Aconitum coreanum (Levl.) Raipaics can regulate the functional status of skin and make the others work better. More information on the prescription rules has previously been published.13

Further, the liquid Gallus domesticus Brisson is the excipient that combines all the TCM ingredients. It not only forms a membrane when applied to the face, it also has considerable nutritive effects. Finally, apart from starch, rice water contains various vitamins needed by the human body. Records show that in ancient China, rice water was used directly to wash the face so as to moisten and whiten the skin.14 It is important to note that Angelica dahurica, which was used commonly for skin whitening by the ancient Chinese, is prohibited today from use in cosmetics due to its potential to cause photosensitivity that may result in phototoxic dermatitis.15 Also, Aconitum coreanum (Levl.) Raipaics is prohibited due to the hypaconitine it contains,16 and the use of Asarum Heterotropoides Fr.var.mandshuricum Kitag is banned because the safrole in its essential oil is toxic.17, 18

In ancient Chinese history, several variations of Qi Bai Gao skin-whitening treatments were recorded in medical classics such as the Tai Ping Sheng Hui Fang,19 Pu Ji Fang,20 Wei Sheng Bao Jian,21 and Yi Fang Lei Ju.22 It is very common for the same formulas to be listed by different names. Further, in addition to Tingzi, mentioned previously, other drug forms include powder agents such as TCM mixers and ointments, or water decoctions that blend the TCM mixers with suet or tallow.

Present day composition analysis and biological research on the TCM ingredients used in Qi Bai Gao have revealed a close relationship between the chemical composition of the ingredients and skin-whitening efficacy (see Table 3). In fact, this formula or TCM ingredients in the formula have been widely used in many modern Chinese cosmetic brands such as the Herborista, Chandob, Magic (MG)c, and by the company Shanghai Inoherb.

Current Use and Safety Considerations

In the current Chinese skin care market, there are two major categories for skin whitening from the perspective of properties of the additives: vitamin C or its derivatives and arbutin; or TCM ingredients. Basically, the mechanism of these additives is to inhibit the tyrosinase activity and/or melanocyte growth to achieve skin whitening. Statistics on TCM ingredients contained in skin-whitening products show that more than 20 types are used most often, including Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Bletilla striata(Thunb.) Reichb.f, Angelica sinensis, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., ginseng, etc.23

However, note that with technological developments, a large number of TCM ingredients have shown toxic side effects. Early in the 1990s, more than 500 TCM ingredients such as Solidago decurrens Lour. and Erycibe obtusifolia Benth. were specified as toxic in medical references, which attracted much attention.24 In response, in 2003, the Chinese Ministry of Health specified 563 kinds of TCM ingredients for use in cosmetics.25 Furthermore, 78 kinds of toxic TCM ingredients were prohibited from cosmetic use.18

In relation, although some ingredients are considered eligible for cosmetic use, a considerable number of TCM ingredients with skin-whitening efficacy such as Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, tea, Angelica sinensis and Pueraria edulis Pampan., have been found to promote skin allergy to some extent.26 Therefore, not all the TCM ingredients allowed for use in skin-whitening cosmetics are entirely safe. In fact, such problems are encountered frequently with TCM ingredients as well as herbal extracts in cosmetic products in general.

Challenges in Applying TCM Ingredients

Similar to other TCM cosmetics, skin-whitening products are gaining popularity. However, there are many problems yet to be solved in this field. Technically speaking, the formula forms of present TCM skin-whitening products differ significantly from those recorded in historic medical references. Products manufactured according to ancient methods are no longer suitable for modern use. Furthermore, it is difficult for ancient forms or drugs to fit the skin feel and aesthetic consciousness of modern consumers. It is also necessary to solve the problem that most TCM extracts with effective constituents carry dark colors and unfavorable scents. Therefore, it is an overall challenge for cosmetic products with TCM extracts to maintain the skin- whitening efficacy indicated by ancient Chinese prescriptions while conforming to modern sensory requirements.

However, it is easier today to conduct research on and prove the biological functions of a single TCM ingredient—although challenges lie in how to apply modern scientific methods to prove the rationale of the TCM ingredient combinations and proportions prescribed in ancient formulae. One successful example is that the anti-leukemia mechanisms of the ancient formula Realgar-Indigo are explained by a modern scientific bioassay, which is related to synergistic effects of the ingredients in different herbs of the formula.27

Another consideration is the common view, both in academia and folklore, that the quality of a TCM ingredient is closely related to the region in which it was grown. For instance, ginseng from the Changbai Mountain area is regarded as the best,28 while Angelica sinensis from County Min, of the Gansu Province, is considered top-level.29 In relation, research has shown that the content of effective constituents in TCM ingredients of the same species can vary significantly due to regional differences. Thus, when TCMs of the same species are applied in skin care to solve a specific problem, some may be effective whereas others may not. Quality also diverges between cultivated and wild TCM ingredients of the same species. For example, the glycyrrhizic acid contained in wild Inner Mongolia licorice is 7.28%—significantly higher than the 2.78% contained in cultivated Inner Mongolia licorice.30 Hence, it is crucial for R&D institutions to search for TCM ingredients with good quality to ensure the level of effective constituent contained in the TCM extract.

As is well-known, sensory indicators such as appearance, aroma, texture and skin feel are of great importance in cosmetic products. However, as noted, since the composition of TCM ingredients is very complex, extracts of the effective constituents usually carry a dark color and/or unfavorable scent. For instance, Rheum officinale extracts and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge extracts are dark brown in color and Angelica sinensis extracts carry a strong herbal, sour and bitter flavor. Techniques including supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, natural clarification technology, microwave-assisted31 or enzyme-assisted extraction methods32 and membrane condensation33 can partly improve the appearance and scent of TCM extracts.

In addition, features such as temperature, optical and pH instabilities have significantly confined the application of TCM extracts in cosmetic products. Nowadays, researchers are still puzzled by these technical problems and currently, attempts are being made to overcome these challenges in many ways, including enveloping the unstable constituents using microemulsions, liposomes, microcapsules or micelle technologiecs to increase their stability.34, 35

Finally is the challenge of how to make the use of TCM ingredients rational and sustainable. The extensive and unplanned exploitation of wild TCM ingredients during recent years has resulted in serious vegetation destruction and land desertification. For instance, licorice is one TCM ingredient used commonly in skin-whitening cosmetic products. It usually grows in areas of challenging natural environments like Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang Province.36 Sustainable utilization is not impossible but due to irrational exploitation, the surrounding vegetation and ecological environment has been damaged to some extent. In fact, due to this fragile ecosystem, it is difficult for perennial plants such as licorice to grow as extensively as it has in the past in the central and western area of Inner Mongolia.

Another example is Saussurea involucrate, a botanical that grows in plateaus of the Xinjiang Province, which has been specified by the Chinese government as a species in imminent danger. Wild Saussurea involucrate can hardly be found in natural fields any more due to immoderate and successive exploitation by human consumption.37 Efforts have been made to improve the situation through artificial cultivation on a large scale basis, and by applying biological engineering technologies such as plant callus cultures. One possible way to reasonably utilize plant resources would be to adopt artificial cultivation techniques to imitate the wild environment as much as possible, then collect TCM plants in accordance with their natural growth pattern.

Summary

For thousands of years, white and fair skin have been considered symbols of beauty by East Asian women. Among the prescriptions for beautification purposes recorded in Chinese historic medical references, more than 25% are for skin-whitening and skin-lightening benefits. Today, skin-whitening cosmetics continue to grow in popularity. Through the analysis of the most well-known formula Qi Bai Gao, this article provides an introduction of the properties of TCM ingredients with skin-whitening efficacy, their prescription rationale and their various forms. Further, the challenges of applying TCM ingredients in skin care products are also discussed. With technological developments in TCM research and development, advanced methods could emerge to help improve the preparation of unstable ingredients and remove the unpleasant colors and flavors of the TCM extracts, giving rise to more reliable skin-whitening products with an improved sensory feel. In addition, with the enhancement of artificial cultivation as well as the deepening understanding of TCM prescription theory by scientists, the application of TCM in cosmetic products will have broader prospects.

References

Send e-mail to [email protected].

- X Zhang, A lighter shade of pale, China Daily, available at www.chinadaily.com.cn/usa/weekly/2011-09/23/content_13775846.htm (Accessed Aug 16, 2012)

- XP Wen, Establishment of the database on ancient TCM beauty prescriptions and analysis, J Traditional Chinese Medicine Literature 25(2) (2007)

- JL Xu, Exploration on the application of Qu Gan Zeng Fang, Shaanxi Traditional Chinese Medicine 24(1) (2003)

- XW Zou and ZS Jiang, Advances in studies on botanical inhibitors of tyrosinase, Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 35(6) (2004)

- GZ Xu, Yu yao yuan fang (prescriptions of royal drug museum) (AD 1271–1368), Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (1992)

- P Wang, New application of the ancient formula Qi Bai Gao, J Gansu College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 24 (4) (2007)

- PG Xiao, YY Wang, XM Gao, and Y Dang, eds, Traditional Chinese Medical Beauty Care, Beijing: China Science and Technology Press (2000)

- KJ Chen and CS Li, Selected Chinese medicine beauty jianpu, Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (1992)

- FL Huang and SX Yan, eds, Practical Chinese medicine beauty studies, Liaoning: Liaoning Science and Technology Publishing House (2001)

- HY Tang, GB He and XL Zhou, Comparative studies on tyrosinase inhibitory activities of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of cosmetic whitening traditional Chinese medicines, Chinese Pharmaceutical J 40(5) 342-343 (2005)

- JY Zhang and ZZ Lu, Distinguishing between Typhonium giganteum Engl. and Aconitum coreanum(Levl.) Raipaics which have the same alias, J Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine 26(2) (Jun 2007)

- Ibid Ref 6

- HL Li, History, Characteristics and Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Cosmetics, Cosmetics & Toiletries, 127 3 (2012)

- Y Li, ed, Ancient Chinese make-up formulations, Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2008)

- LK Zhang, J Zhu and WZ Shi, Analysis on skin allergy caused by topical traditional Chinese medicine, Heibei Traditional Chinese Medicine 33 (11)1736–1739 (2011)

- QW Ni, Testing and research on the toxic ingredients of Aconitum coreanum(Levl.) Raipaics, Zhejiang J Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, 9 (6) (1999)

- SW Huang, The pharmacological toxicity and clinical application of Asarum Heterotropoides Fr.var.mandshuricum Kitag, Anhui Medical and Pharmaceutical Journal, Dec, 7 (6) (2003)

- TG Zhao, ed, Hygienic standard for cosmetics, Beijing: Military Medicine Science Press (2007)

- HY Wang et al, eds, Tai ping sheng hui fang (Taiping holy prescriptions for universal relief) [AD 992], Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (1958)

- S Zhu et al, eds, Pu ji fang (Prescriptions for universal relief) [AD 1406], Liaoning: Liaoning Science and Technology Publishing House (2007)

- TY Luo, WY Wu and HS Sun, eds, Wei sheng bao jian (Encyclopedia of Health) [AD 1281], Beijing: China Medical Science Press (2011)

- LM Jin, Yi fang lei ju [1445 A.D.], Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (2007)

- Mintel’s GNPD, www.gnpd.com, search criteria: skin care products (Jan-Jun 2012)

- XZ Guo et al, eds, A dictionary of poisonous Chinese herbal medicines, Tianjin: Tianjin Science and Technology Translation and Publishing Corp (1992)

- Ministry of Health, List of ingredients for cosmetic use in China, Beijing: Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China (2003)

- JS Zou, Reviews on allergic reactions caused by traditional Chinese medicines, Practical Clinical J of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine 6(4) (2006)

- L Want, GB Zhou, P Liu et al, Dissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal formula Realgar-Indigo naturalis as an effective treatment for promyelocytic leukemia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 4826–4831 (2008)

- Authentic and genuine medicines, Modern Chinese Medicine 8(6) (2006)

- H Lu et al, Laboratory study on the effects of four kinds of Angelica sinensis Diels from different places: coagulation function, Chinese J Traditional Medical Science and Technology 9(4) (2002)

- CM Zhou et al, Comparison of glycyrrhizic acid content in wild and cultivated Ural licorice, J Chinese Medicine Materials 25(12) 861-862 (2002)

- A Delazar, L Nahar, S Hamedeyazdan and SD Sarker , Microwave-assisted extraction in natural products isolation, Methods in Molecular Biology, 864:89-115 (2012)

- M Puri, D Sharma and CJ Barrow, Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactives from plants, Trends in Biotechnology, 30(1) 37-44 (2012)

- G Romanik, E Gilgenast, A Przyjazny and M Kaminski, Techniques of preparing plant material for chromatographic separation and analysis, J Biochem Biophys Methods 70(2) 253-61 (Epub Oct 11 2006; print Mar 10, 2007)

- A Bettencourt, AJ Almeida, Poly(methyl methacrylate) particulate carriers in drug delivery, J microencapsulation 29(4) 353-67 (2012)

- W Liu, XL Yang and WS Ho, Preparation of uniform-sized multiple emulsions and micro/nano particulates for drug delivery by membrane emulsification, J Pharmaceutical Sciences 100(1) 75-93 (2011)

- CQ Hu, FH Li and LH Fan, Investigation and suggestions on wild traditional Chinese medicine resources in the central and western inner Mongolia, in Anthology of Thesis for the 4th Annual Natural Science Academic Meeting of Inner Mongolia (2007) pp 55-58

- XF Yuan, B Zhao and YC Wang, Advances in studies on Saussurea involucrata, Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 35(12) (2004)